Module 1: Who Is Chol Soo Lee?

How does the life of Chol Soo Lee teach us about the roles each of us can play in creating a more just society?

On the still-bright summer evening of June 3, 1973, shots rang out at a bustling intersection of San Francisco’s Chinatown, teeming with locals and tourists. The crowd watched in horror as a gunman shot three bullets into a man and fled the scene. The victim was a reputed Chinatown gang advisor, Yip Yee Tak. His killing followed a string of more than a dozen unsolved murders in the ongoing war between two rival Chinese gangs. This time, the city’s mayor vowed to catch the killer. Within days, police arrested Chol Soo Lee.

This module is about how a poor and isolated Korean immigrant was racially profiled and wrongfully convicted of murder in San Francisco, California, in the 1970s. But after a journalist exposed this injustice to the public, strangers rallied to his side, building an unprecedented pan-Asian American social movement to “free Chol Soo Lee.”

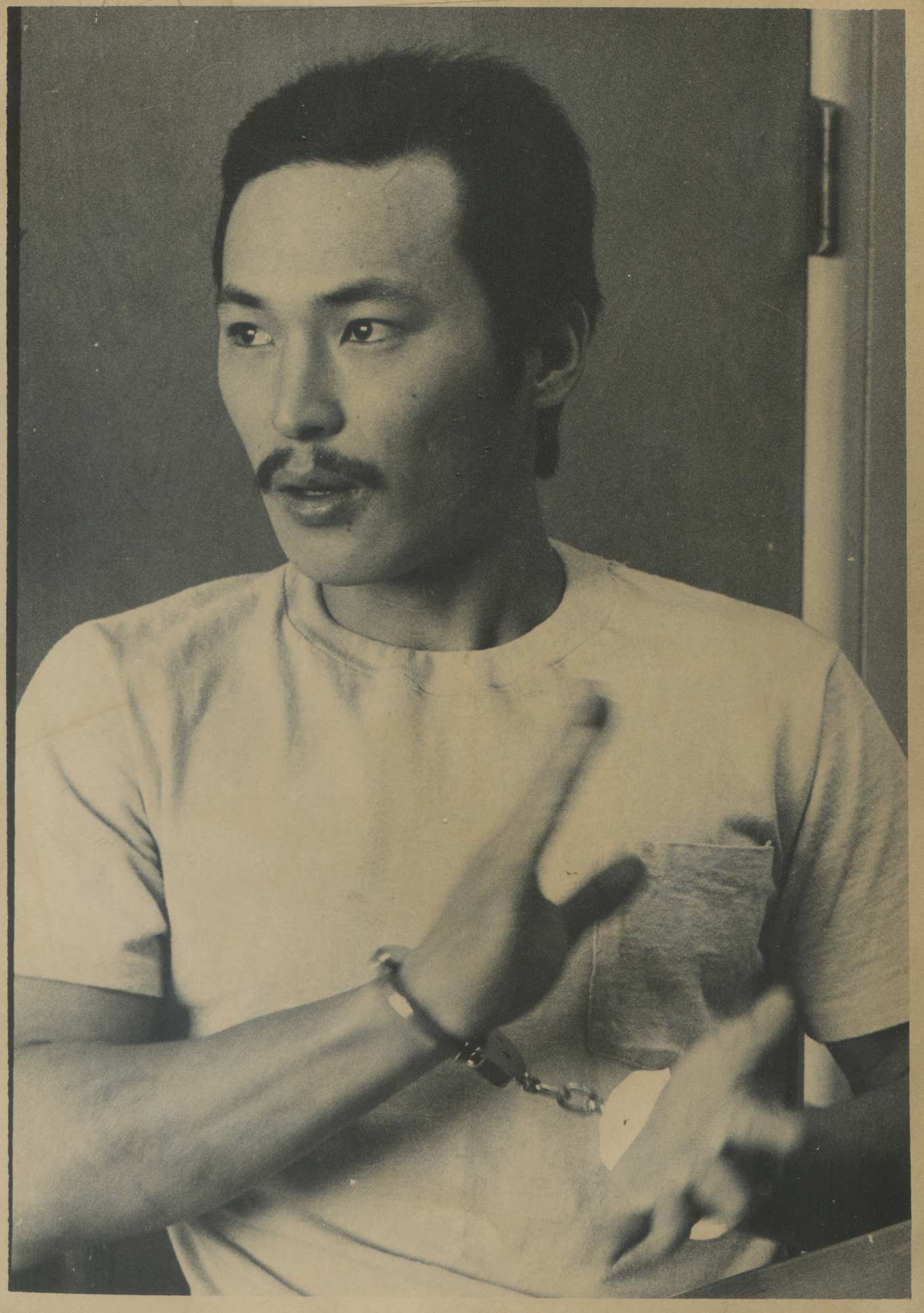

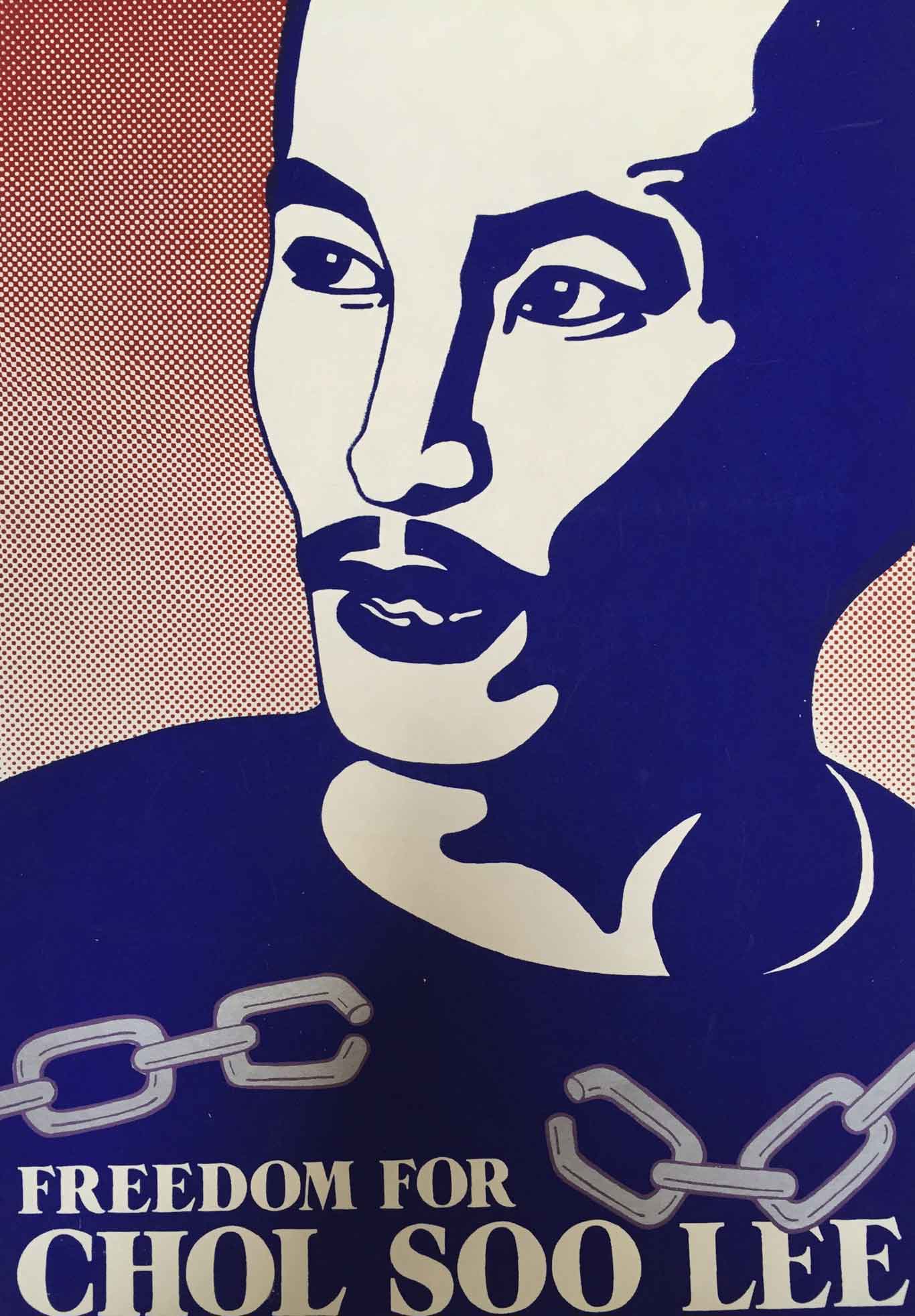

Image 44.01.01, 44.01.02 — This 1977 photo (left) of Chol Soo Lee, taken in prison, became the inspiration for artist Wes Senzaki’s poster created for the movement to free Chol Soo Lee.

Courtesy of K.W. Lee. Metadata ↗

Courtesy of Wes Senzaki/Japantown Art and Media. Metadata ↗

What role did Chol Soo Lee’s race play in his murder conviction?

Why did so many Asian Americans of different generations, political ideologies, and ethnic groups devote themselves to fighting for a stranger, Chol Soo Lee?

What can people today learn from the story of Chol Soo Lee?

The Injustice

Chol Soo Lee was twenty years old when police arrested him for the Yip Yee Tak murder in 1973. Chol Soo had been involved in a gun incident the day before the murder, and that’s why he initially caught the police’s attention. But he insisted on his innocence. “I am a Korean, and Chinese is Chinese. And there’s no way possible I could have been any part of a Chinatown gang,” he said. 1

However, Chol Soo could not afford the support he needed in court. His public defender and, later, a court-appointed attorney did little to help his case, failing to locate witnesses who could corroborate his alibi. At his murder trial, the prosecution presented little material evidence and instead relied on the eyewitness testimonies of three white tourists, who saw the killer for mere seconds from about forty-five feet away.

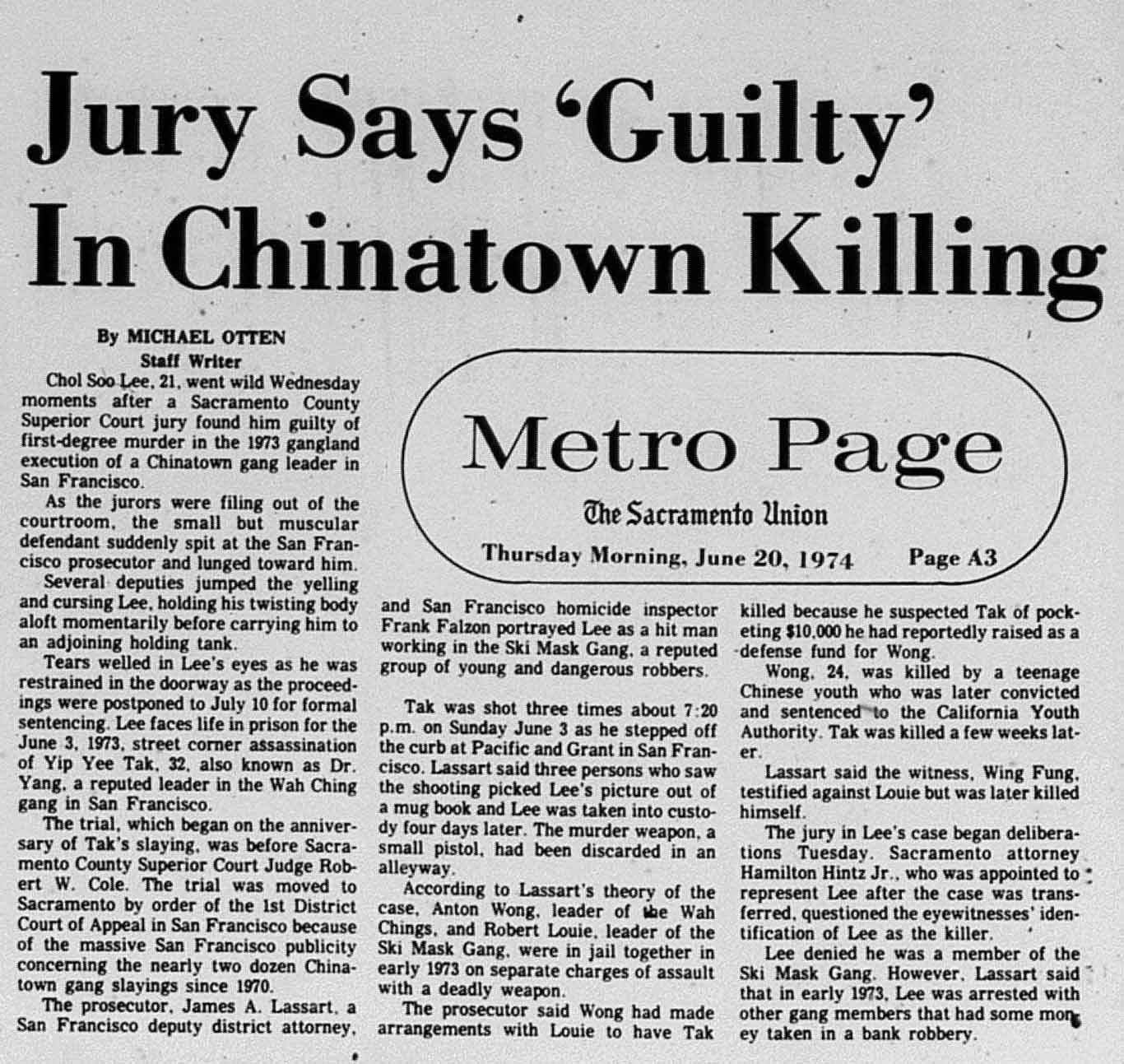

On June 19, 1974, a jury convicted Chol Soo of first-degree murder, based largely on questionable eyewitness testimony. He was sentenced to life in prison at one of California’s then-most-violent prisons, Deuel Vocational Institution.

Text 44.01.03 — This article in the Sacramento Union, dated June 20, 1974, records Chol Soo Lee’s reaction to his conviction for the murder of Yip Yee Tak.

Courtesy of K.W. Lee. Metadata ↗

As one of the few Asians at the prison, Chol Soo was vulnerable and found himself fighting to survive amidst warring racial gangs in the prison. Four years into his sentence, on October 8, 1977, Chol Soo and Morrison Needham, a member of a neo-Nazi prison gang, had a confrontation in the prison yard. During this knife fight, Chol Soo killed Needham and told authorities he acted in self-defense. Nevertheless, he was charged with first-degree murder. Because this was his second murder charge, he would face the death penalty.

“Alice in Chinatown”

Chol Soo Lee didn’t know it yet, but a newspaper reporter named K. W. Lee had begun to look into his case in 1977, after receiving a tip from a Korean American social worker. A Korean immigrant himself, K. W. was the Sacramento Union’s chief investigative reporter. He soon uncovered facts that suggested Chol Soo was wrongfully convicted. When he heard of the second murder charge, the journalist rushed to meet and speak with Chol Soo.

“Deep in my heart I am saddened by what you have gone through as a Korean youth in this country,” the journalist wrote in his letter to Chol Soo. Acknowledging that he may have been too late, K. W. offered what he could to support him. “I want to write about the problems you have run into as a bewildered and helpless Korean boy in America. Maybe … society will listen.” 2

The two men quickly established a rapport. Feeling alone for much of his life, and lacking the support of his mother while in prison, Chol Soo now saw another lifeline.

“[K. W. Lee] single-handedly … has given me hope when there was no hope,” said Chol Soo. Having the concern and attention of the journalist made him realize, “‘You’re not just some guy off the street, not just some prisoner. But you’re a Korean American immigrant whose rights [have been] so violated, and that needs to be corrected.” 3

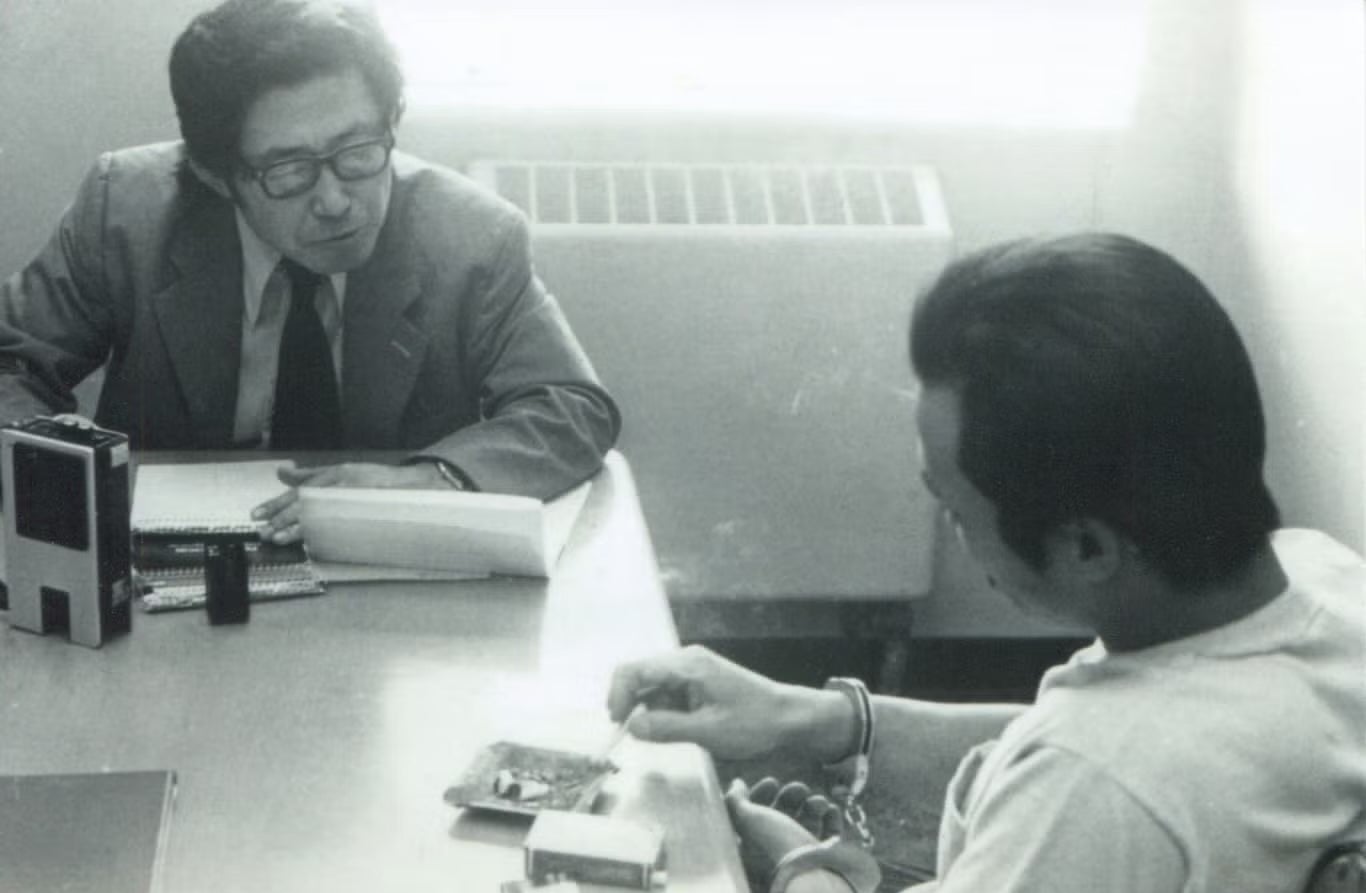

Image 44.01.04 — Sacramento Union investigative reporter K. W. Lee interviews Chol Soo Lee at Deuel Vocational Institution in Tracy, California, in 1977.

Photo by Jerry Rainbolt/Courtesy of K. W. Lee. Metadata ↗

In interviewing Chol Soo, K. W. discovered the saga of a bewildered Korean immigrant boy whose life became a series of nightmares upon immigrating to the United States. Born in the middle of the Korean War, Chol Soo had grown up with his aunt and uncle’s family in Korea, after his mother was banished by her own parents for having him out of wedlock. He never knew his father. His mother ended up immigrating to the US after marrying, and later divorcing, an American soldier. In 1964 she summoned twelve-year-old Chol Soo to come live with her in San Francisco. By the time he came to join her, she was a struggling single mom with two other children.

Meanwhile, at school, Chol Soo faced his own problems. Peers bullied him, but he fought back. He even landed in juvenile hall after kicking a school vice principal during an angry outburst. Later, he was sent to a state mental hospital, where he was mistakenly diagnosed with schizophrenia. He became a chronic runaway, committing petty crimes to survive on the streets. During his interview with K. W., he described himself as “lost.”

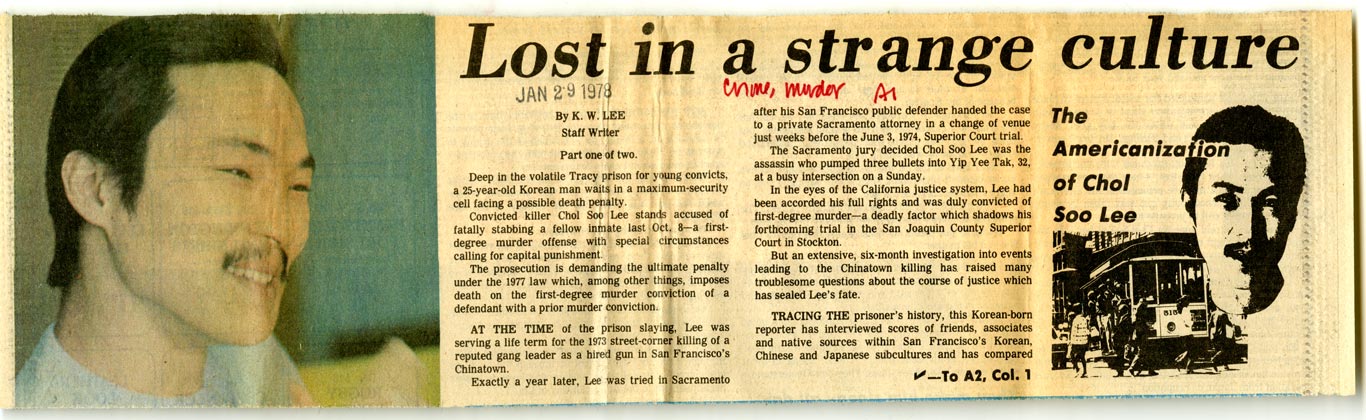

The journalist’s six-month investigation led to a stirring two-part newspaper series, published in January 1978 under the headlines “Lost in a Strange Culture” and “Alice-in-Chinatown Murder Case.” 4 The stories exposed gaping holes—and racial bias—in the conviction of Chol Soo.

Text 44.01.05 — In this 1978 Sacramento Union article, K. W. Lee humanizes the plight of Chol Soo Lee, who had an optimistic view of America upon immigrating, but ended up serving a life sentence in one of California’s most violent prisons.

Courtesy of UC Davis Shields Library/Sacramento Union Archive. Metadata ↗

In his investigative report, K. W. found that Chol Soo did not match eyewitness descriptions of the killer, who was said to be as tall as five-foot-ten. Chol Soo was at most five-foot-four and also had a mustache, a facial feature that not a single witness mentioned. The reason was obvious to K. W., who said that for the white eyewitnesses, “Chinese, Japanese, Koreans, ‘they all look alike.’ ” Underscoring this point, at the murder trial, the police officer who arrested Chol Soo mistakenly identified him as “Chinese” from the witness stand, but Chol Soo’s own attorney did not even object to this error. 5 This indicated racial bias and overlooked errors from the beginning of the case.

The Movement

Through K. W. Lee’s reporting, Chol Soo Lee’s story reached a wide public audience. His articles were photocopied and also translated into Korean. Korean immigrants saw themselves in different aspects of his story and felt compelled to act.

Jay Kun Yoo, a law school graduate based in Davis, California, said he and other Koreans could identify with Chol Soo as a child of the Korean War, alone and abandoned on both sides of the Pacific, and needing their help. He and Grace Kim, an educator and social justice activist also based in Davis, formed the Chol Soo Lee Defense Committee to raise awareness about Chol Soo’s case as well as funds for new defense attorneys.

Support from the Korean American community served a larger purpose. “We wanted to show America and the legal system that we Korean Americans love justice and can organize ourselves to defend our rights,” Yoo said. 6

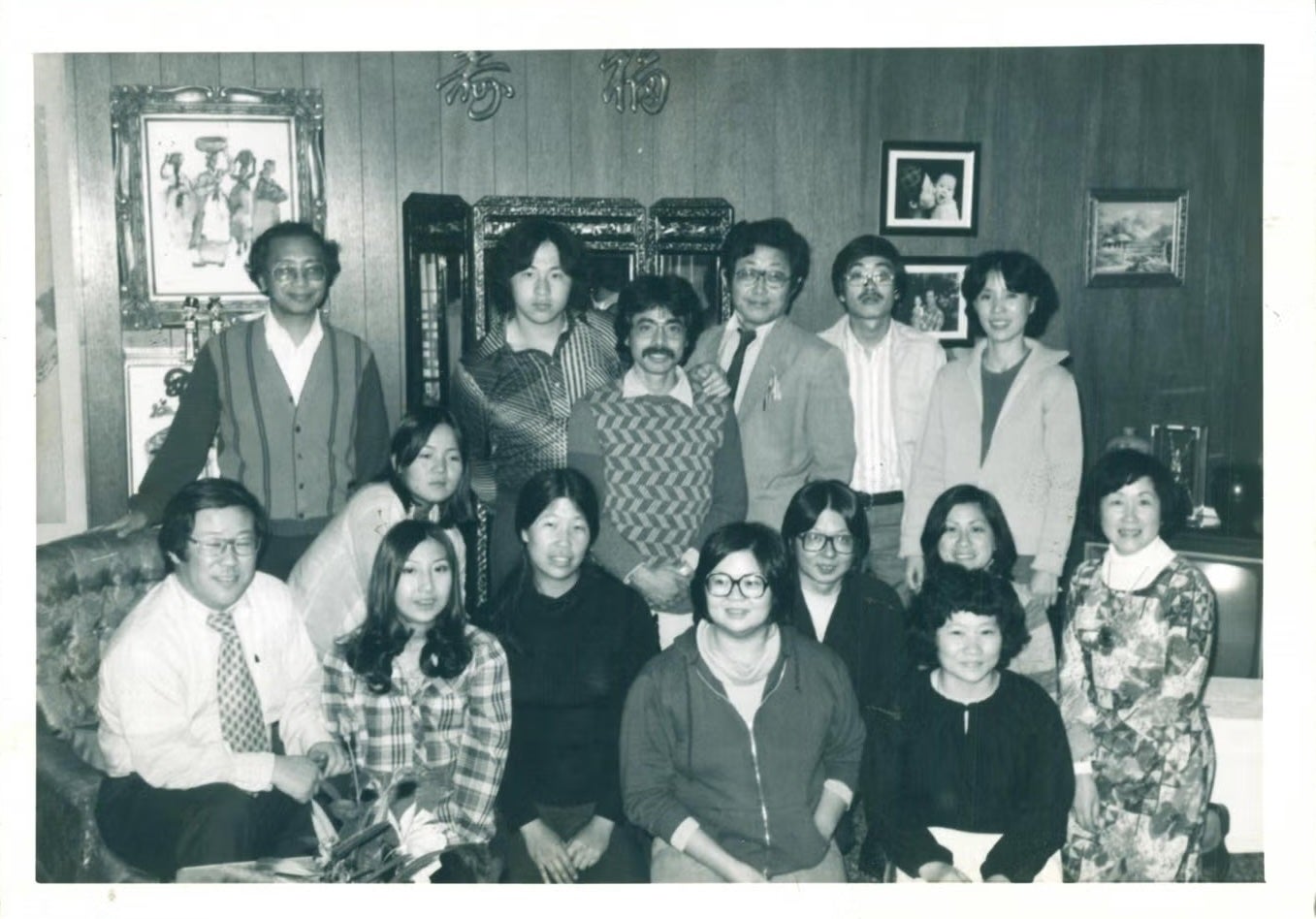

Image 44.01.06 — Activists gather in Sacramento for one of the earliest meetings of the Chol Soo Lee Defense Committee in 1978.

Courtesy of K.W. Lee. Metadata ↗

The group started small, with mostly first-generation Korean Americans in the Sacramento area. But soon, the movement for Chol Soo grew into a pan-Asian American movement that spread to other parts of California and then across the nation. The Sacramento Union articles reached second-, third-, and fourth-generation Chinese, Japanese, and Korean Americans. Many were college students who heard of Chol Soo in their ethnic studies classes or at gatherings with activists and social workers. They connected their experiences in the civil rights, Black Power, anti-Vietnam War, and ethnic studies movements to the struggle to free Chol Soo.

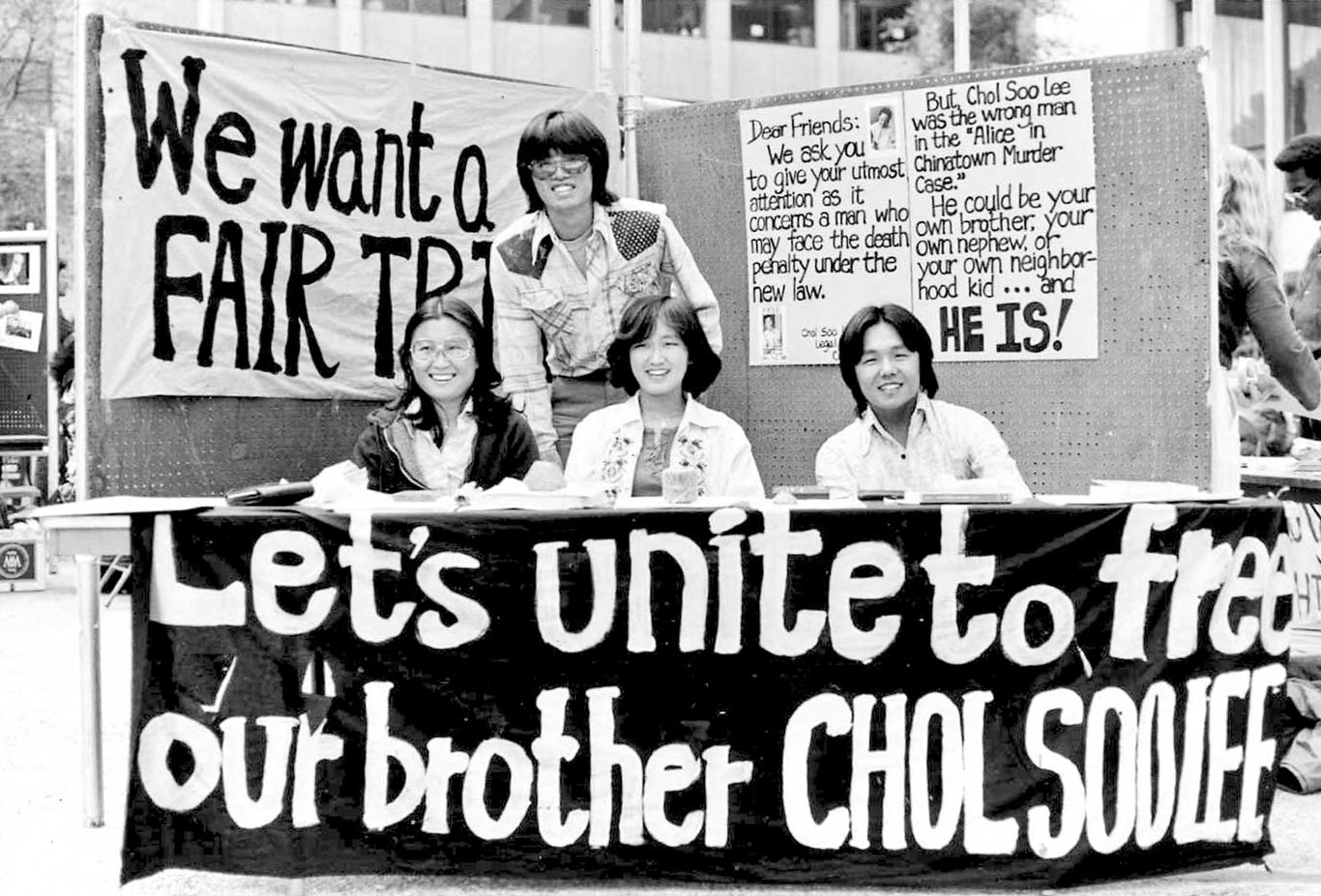

While Kim and Yoo focused their outreach in Korean churches, appealing to congregants for support and donations, the young activists raised awareness in their own ways. For example, they set up information booths at Asian American community and college events, and held fundraising dance parties, car washes, and hot links sales. University of California, Berkeley, college activist Jeff Adachi even wrote a poem, “The Ballad of Chol Soo Lee,” that was made into a song and recorded on a vinyl record.

At courthouse protests, these seemingly disparate community groups came together. Korean immigrant grandmothers, in their traditional silk dresses, stood alongside Asian American college students, with their blue jeans and feathered hairstyles.

Ranko Yamada, a leading activist in the movement, made a slideshow to educate members of the Asian American community about the case and showed striking images of this multigenerational support. In her narration for the slideshow, she described the unity of this growing movement to free Chol Soo Lee as the “struggle of an entire people … It is a fight for our own freedom, as well.” 7

Image 44.01.07 — Young activists set up an informational and fundraising booth at a local event in San Francisco, circa 1978.

Courtesy of Gail Whang. Metadata ↗

As the young activists confronted racism in their own lives, they saw something of themselves in Chol Soo and responded to this feeling of shared humanity and struggle. “He could be your own brother, or your own nephew, or your own neighborhood kid .… and he is,” activists would write on posters publicizing the case. They knew that Chol Soo’s experience of separation, abuse, bullying, mistreatment, and racial bias were linked to their own experiences in the United States.

“[Chol Soo] really was a symbol of an expression for Koreans who had been feeling some discrimination, some hardship in this country, and not having a voice or [a way] to speak up about some of the injustices they were feeling,” said Gail Whang, a third-generation Korean American who helped organize protests in Northern California. “I remember we … organized the halmeonis (“grandmothers” in Korean) to come out. They had so much compassion and fight for this wrongdoing. At the same time we had halmeonis, we had young students. At our rallies, we had young and old.” 8

Asian American studies professor Richard Kim called this mobilization an important event in Asian American history because “people of different classes, ethnicities, religions, levels of education, generational histories, political affiliations, and geographical locations came together in common political cause.” 9

Legal Roller Coaster

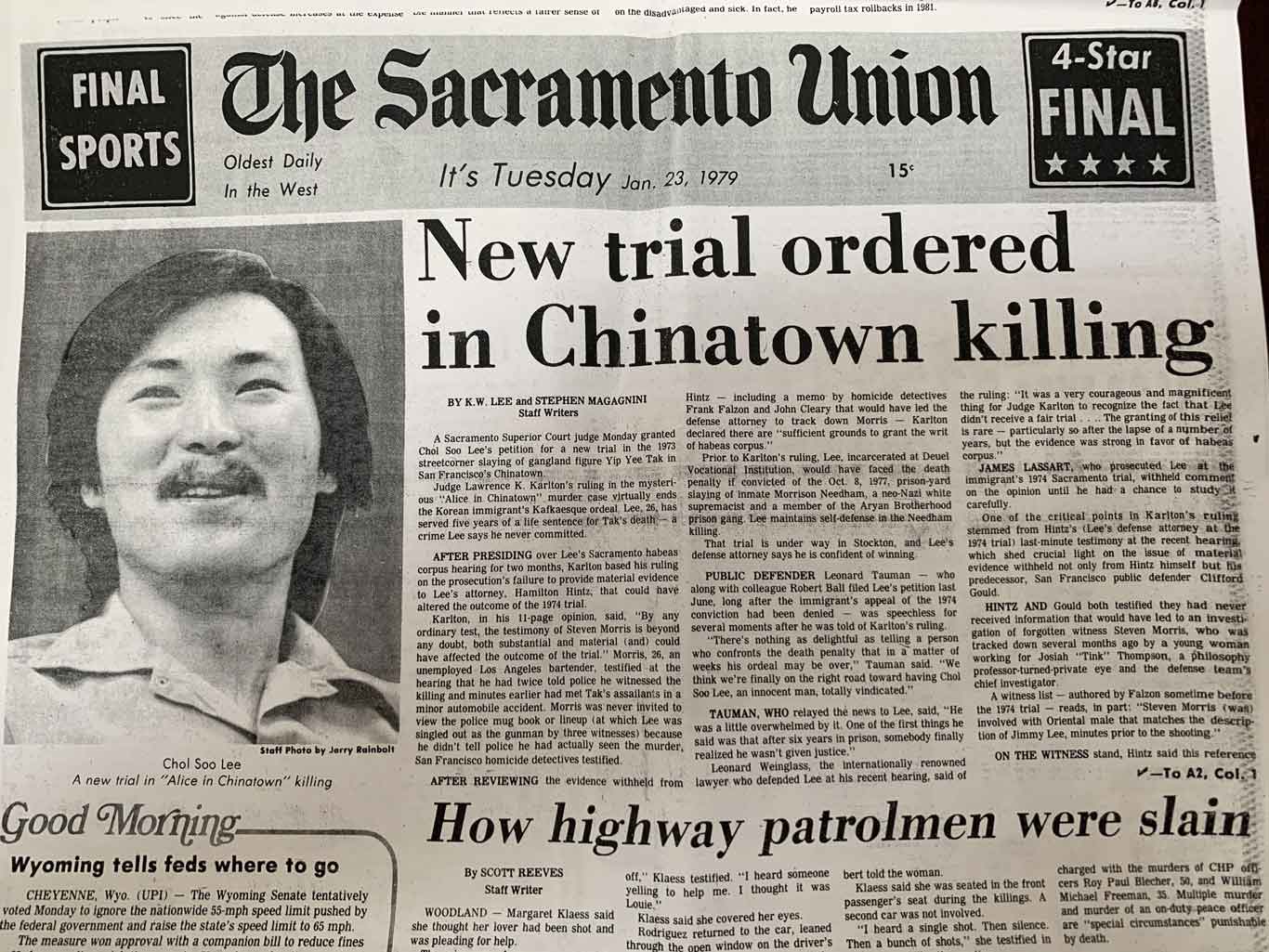

The multigenerational grassroots efforts raised enough money to hire nationally renowned criminal defense lawyers and a private investigator, who uncovered new evidence and witnesses. In 1979, about a year after K. W. Lee’s first articles on the Chol Soo Lee case ran, a Sacramento court overturned the Chinatown murder conviction in a remarkable victory.

Text 44.01.09 — K. W. Lee and fellow Sacramento Union staff writer Stephen Magagnini provided persistent coverage of the Chol Soo Lee case, including discovering a crucial witness in the Chinatown murder case. Thanks to that witness, a Sacramento judge ordered a new trial.

Courtesy of K.W. Lee. Metadata ↗

But a month later, Chol Soo was tried and convicted of first-degree murder for the prison-yard slaying. He was sentenced to death. In an interview from death row, Chol Soo spoke somberly about how it felt like “dying each day as you live.” But he also described the support of so many people on the outside as “one of the most tremendous and beautiful experiences of my life. The poor man cannot expect to get justice by himself, but he needs people to … to try and get justice.” 10

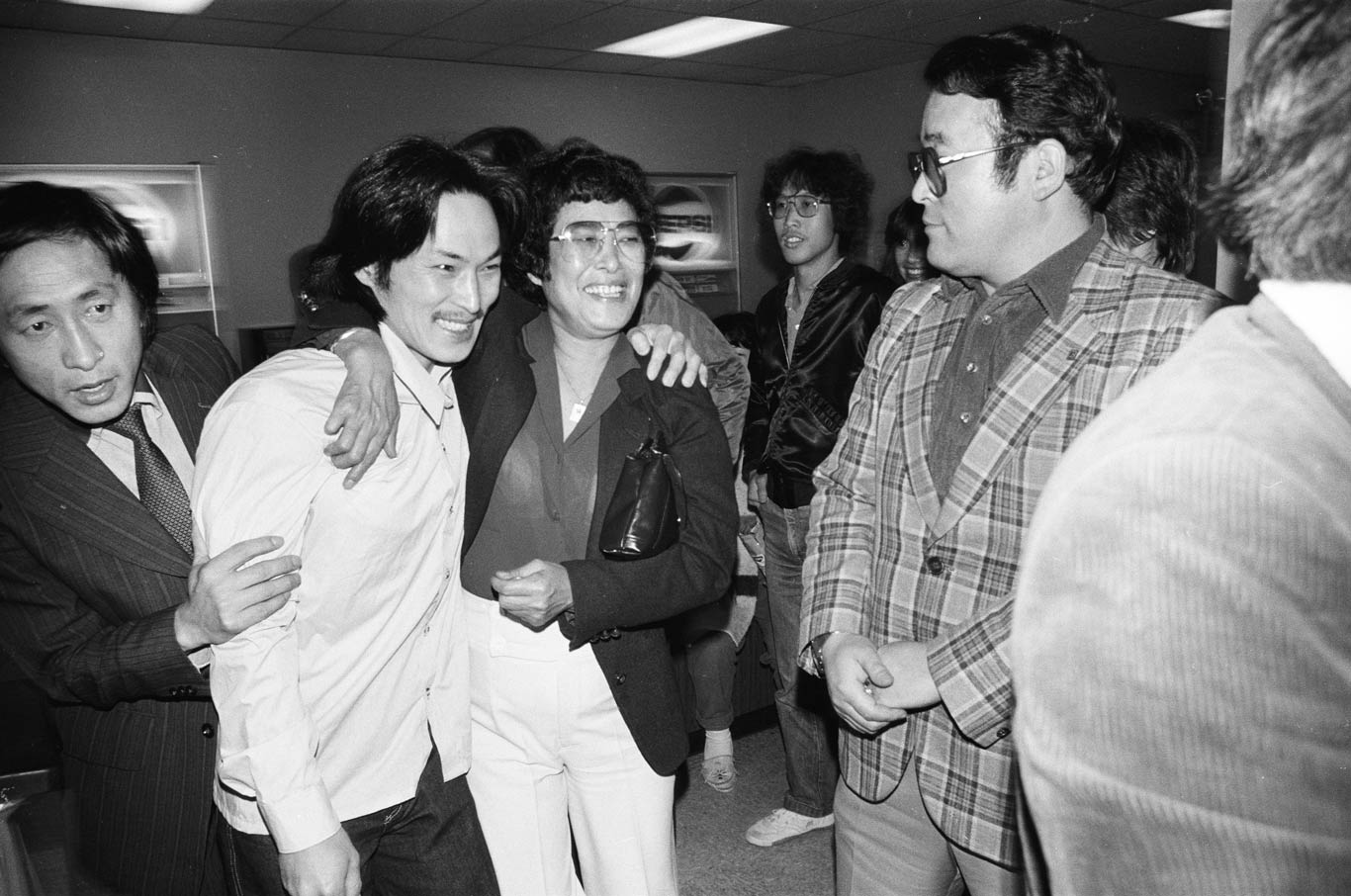

People did not give up their fight to free him. In 1982 the San Francisco district attorney retried Chol Soo for the Chinatown murder, and his supporters packed the courtroom every day. Even though the prosecution called the same witnesses from the first trial, Chol Soo’s lawyers provided a skillful defense that cast doubt on the credibility of those witnesses. On September 3, 1982, a San Francisco jury delivered its verdict. Unlike in 1974, Chol Soo heard the words “not guilty” and a courtroom of supporters erupting into cheers.

He would remain in prison for several more months, waiting for an appeals court to reverse the murder conviction in the prison-yard case. Then, on March 28, 1983, Chol Soo took his first steps into freedom, after ten years of unjust incarceration. “There is no money that could ever repay what the people have done for me,” said Chol Soo, thirty years old at the time. “The freedom they gave me came from their hearts. The best way I can repay the Asian community is to make a good example of myself.” 11

Image 44.01.10 — Chol Soo Lee, flanked by his mother, walks into freedom on March 28, 1983, after 10 years in prison.

Courtesy of Grant Din. Metadata ↗

The Release

Chol Soo Lee’s retrial and release did not mark the end of his saga. Without rehabilitation or reentry programs to assist them outside of prison, people who leave prison often struggle to live outside it. Chol Soo was no exception. He carried with him the trauma from his incarceration and a sense of debt to the community to whom he owed his life.

He turned to drugs for escape. From there, he went in and out of jail for various criminal offenses. In 1991 he started working for a Chinatown gang for the first time in his life, and was tasked with setting a gang’s safe house on fire. However, the arson went awry, and he suffered severe burns, becoming disfigured and disabled. The news devastated his supporters. After agreeing to testify against the gang that hired him, Chol Soo went into a federal witness protection program.

A decade in witness protection gave Chol Soo time to reflect. He returned to San Francisco in 2004, determined to redeem himself in the eyes of the community that fought for his freedom. He started sharing his story, speaking publicly about his case and writing his memoir. He finally revealed the demons that haunted him—his dehumanizing prison years, scars from an abusive mother, a life of loneliness, and the daunting responsibility of being a symbol for a landmark Asian American movement. “I never asked to be a cause,” he said at a 2006 symposium at the University of California, Davis. “I only asked to be free from the cage of injustice.” 12

Many of the activists who rallied for Chol Soo went on to become lawyers, community leaders, elected officials, and social justice advocates. College activist Jeff Adachi graduated, became a lawyer, and later served as the elected public defender of San Francisco. Adachi attributed his career to Chol Soo.

“There are many of us who would never have reached the critical understanding of the problems of our society without experiencing the Chol Soo Lee case,” Adachi said. “I can say with certainty that I would not be a lawyer or a public defender, had it not been for Chol Soo Lee …. His struggle was our struggle and though we did not experience the hell that he had to live through, he allowed us to learn from his experience and grow from it.” 13

Image 44.01.11 — Chol Soo Lee died on Dec. 2, 2014, at the age of 62 from health complications related to his burn injuries. Many of those who had rallied to his side decades earlier attended his funeral on Dec. 9, 2014, in San Bruno, California, and laid flowers at this altar.

Courtesy of Kenji G. Taguma / Nichi Bei Weekly. Metadata ↗

Chol Soo was proud of this legacy and grateful for the community who rallied for him. He spent the last chapter of his life advocating for support for at-risk youth and incarcerated Asian Americans, who often fell under the radar in conversations about criminal justice reform. He hoped that sharing his story could raise awareness about the unseen and unheard, as he once was, and inspire social justice movements and people of conscience today.

“I feel that the greatest message that could be given from the Chol Soo Lee movement is … the purity, unselfishness, the integrity of strangers,” said Chol Soo in a 2005 interview. “There are deprived people … even more deprived people than in the past. The need to give is far (greater) than it was in my own time.” 14

Glossary terms in this module

alibi Where it’s used

A claim or piece of evidence that shows a person was somewhere else at the time of a crime and proves their innocence.

grassroots Where it’s used

A term used to describe a movement or organization that starts with everyday people, instead of people in positions of power.

Korean War Where it’s used

From 1950-1953, a war between US-backed South Korea and Soviet/China-backed North Korea that displaced millions of Koreans and flattened cities. The war ended in a stalemate at the 38th parallel that divides Korea today.

racial bias Where it’s used

A discriminatory claim about someone because of their race.

reentry Where it’s used

The process of transitioning back into the community after imprisonment. After imprisonment, formerly incarcerated people often struggle to adjust to life outside of prison.

federal witness protection Where it’s used

A program of the U.S. Department of Justice designed to protect witnesses, along with their family members, before, during, and after legal proceedings whereupon those witnesses have an association with the federal government and provide testimony. Witnesses and their families typically get new identities and relocation support to ensure their safety.

Endnotes

1 Chol Soo Lee, interviewed by Sandra Gin, “A Question of Justice,” Perceptions, KCRA, 1983.

2 K. W. Lee, written correspondence to Chol Soo Lee, November 22, 1977.

3 Chol Soo Lee, interviewed by Sandra Gin, “Untitled K.W. Lee Community Tribute,” 1994.

4 K. W. Lee, “Lost in a Strange Culture,” Sacramento Union, January 29, 1978.

5 K. W. Lee, “Alice-in-Chinatown Murder Case,” Sacramento Union, January 30, 1978.

6 Elaine H. Kim and Eui-Young Yu, East to America: Korean American Life Stories (The New Press, 1996), 289.

7 Ranko Yamada, “Chol Soo Lee Slide Show,” Chol Soo Lee Defense Committee, 1979.

8Julie Ha, “Free, Free Chol Soo Lee,” KoreAm Journal, December 2014.

9 Richard S. Kim, “Introduction,” in Freedom Without Justice, The Prison Memoirs of Chol Soo Lee (University of Hawai‘i Press and UCLA Asian American Studies Press, 2017), 5.

10 Chol Soo Lee, interview by Elaine H. Kim for “Asians Now,” KTVU, 1979, San Quentin State Prison, California.

11 “Chol Soo’s Newest Challenge Is Freedom,” Koreatown Weekly 4, no. 2 (April 1983).

12 Chol Soo Lee, “UC Davis Chol Soo Lee Symposium Remarks,” Courtesy of Richard S. Kim, University of California, Davis, February 22, 2006.

13 Jeff Adachi, “Chol Soo Lee Memorial Eulogy,” recorded by Julie Ha, December 9, 2014.

14 Richard S. Kim, “A Conversation with Chol Soo Lee and K. W. Lee,“ Amerasia Journal 31, no. 3 (2005): 105.