Module 2: Lost in America

How does the life of Chol Soo Lee teach us about the roles each of us can play in creating a more just society?

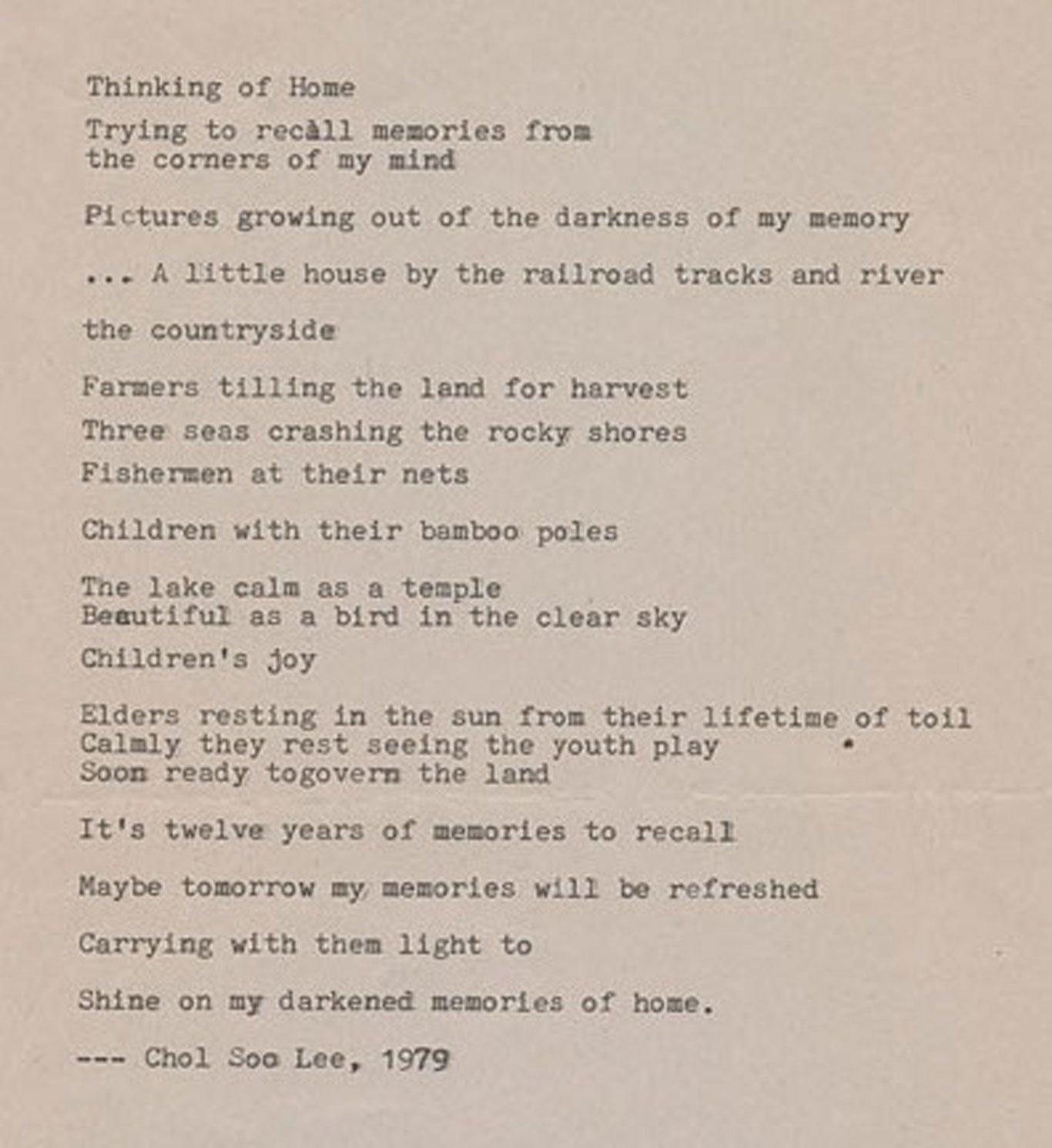

While he was in prison, Chol Soo Lee wrote his first poem, “Thinking of Home.” For Chol Soo, home was his motherland, Korea—a country he left against his own will at the age of twelve. This separation marked one of many severed ties in his life. Over time, he even lost the ability to speak Korean and communicate with his family who had raised him in Korea.

As a child, Chol Soo endured abandonment and family separation, and, later, isolation in his adopted country. Upon arrival, his race, class, and immigrant identities made him an easy target of the US’s school-to-prison pipeline. The traumas of war and migration had a profound impact on his life. This module is about the early life of Chol Soo Lee before his name became a rallying cry for a landmark social movement.

Image 44.02.01 — A childhood photo of Chol Soo Lee, taken in his native Korea.

Courtesy of Ranko Yamada. Metadata ↗

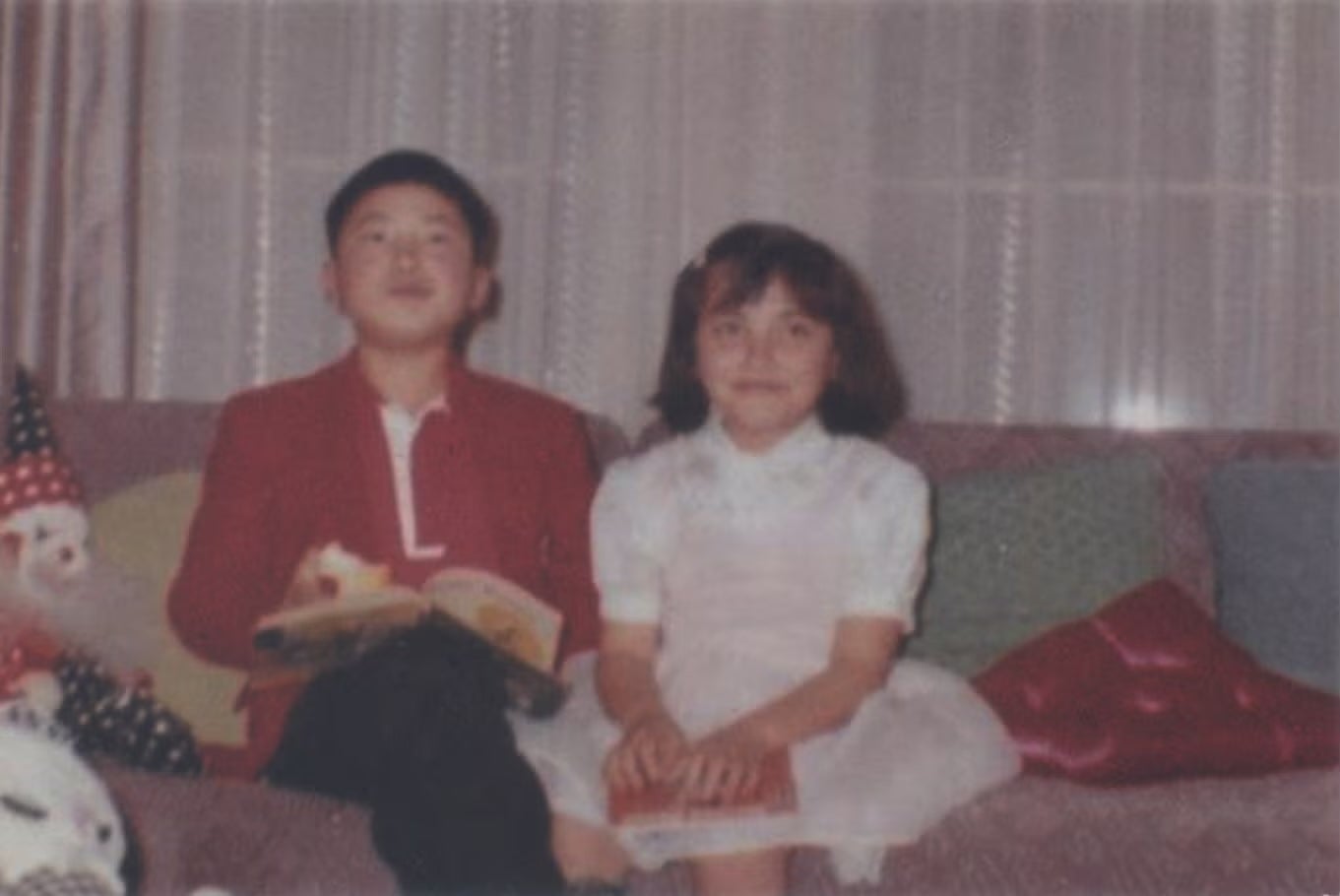

Image 44.02.02 — Chol Soo Lee with his mother and half-sister, in an undated photo.

Courtesy of Ranko Yamada. Metadata ↗

What were some of the difficulties and traumas Chol Soo Lee confronted as a Korean immigrant growing up in San Francisco, California in the 1960s and 1970s?

What roles did his race, immigrant, and class identities play in his entanglement with the criminal justice system at an early age?

What could have prevented the harms that Chol Soo Lee faced?

Child of the Korean War

In his poem, Chol Soo Lee wrote about retrieving memories of home from “the corners of my mind” and “the darkness of my memory.” 1 The poem suggests Chol Soo’s feelings of loneliness and displacement.

While his poem contains memories of farmers tilling the land and fishermen at the water, Chol Soo was never sure about the exact location of his birth. He thought it was perhaps Mokpo in the southwest province of South Jeolla. But he was sure of his birthdate, August 15, 1952, which held great historical significance. He was born on the anniversary of Korea’s independence from Japanese colonial rule—and in the middle of Korea’s devastating civil war. This backdrop of war would shape Chol Soo’s life.

Text 44.02.03 — Chol Soo Lee typed this draft of his poem, “Thinking of Home,” dated 1979, and mailed it to K. W. Lee, who would grow into a life-changing figure in Chol Soo’s life. The poem recalls memories of his motherland, Korea.

Courtesy of K.W. Lee Papers, UC Davis Shields Library. Metadata ↗

The Korean War (1950–1953) had devastating, long-lasting effects on the Korean population. With an estimated three million fatalities and scores of families impoverished and separated from each other, the country was left in ruins. The temporary division of Korea became permanent, resulting in what we now know as North Korea and South Korea.

The United States played a pivotal role in supporting the South during the conflict, and the heavy US military presence in the region continues today. Many Korean women, poverty-stricken after the war, found work near US army bases and ended up meeting and marrying American soldiers. Some immigrated to the US as “war brides,” one of the only ways people could immigrate from Asia at the time.

Chol Soo’s mother, Me Yea Lee, took this path. Because she got pregnant out of wedlock, her parents banished her. She left Chol Soo in the care of her older sister’s family while she found work laundering clothes near a US Army base. There, she met an American soldier who promised to adopt Chol Soo. They married, had a daughter, and prepared to leave for the US. However, they left Chol Soo behind because of problems with his adoption paperwork.

Despite this separation, Chol Soo was cared for. In fact, his childhood in Korea, while living with his aunt, uncle, and cousins, was probably the closest experience he had to a nuclear family and unconditional love. He recalled only a few encounters with his biological mother, and he never knew his father. So, years later, when Me Yea Lee, who had by then divorced her husband, summoned a then-twelve-year-old Chol Soo to live with her in the US, he did not want to go. But his aunt’s family was struggling financially and asked him to send back money and food packages from America.

He felt the weight of responsibility for his family in Korea. “By going to America, I felt that I was my family’s greatest hope to give them immediate relief from their hunger and suffering,” Chol Soo wrote in his memoir. He thought it would be possible to help them; he dreamt of an America that had streets paved with gold. He planned to make enough money to help his family in Korea and then, once rich, rejoin them. “This personal plan seemed so easy that no way could I fail in a country as rich as America,” he thought. 2

Upon arriving in the US, he was in awe of the running hot water in his mother’s apartment and of his first American meal of steak, rice, and canned corn. This was a far cry from his life in post-war Korea, where he collected scrap metal to help his aunt’s family earn money. But even with greater access to food, his single mother struggled to make ends meet. She worked at a cannery by day and as a cocktail waitress by night, leaving little time to spend with Chol Soo and his two half-sisters. Chol Soo missed the only family he ever knew.

Although he had agreed to immigrate in order to help his aunt’s family in Korea, his mother told him that this was not possible. He did not realize that at twelve years old, it was illegal for him to work. He had to go to school instead.

School to Prison

Middle school in San Francisco in the 1960s was a hostile environment for Chol Soo Lee. Peers bullied him for his inability to speak English and for being short for his age. He often fought back, landing him in the principal’s office and leading to beatings from his frustrated mother.

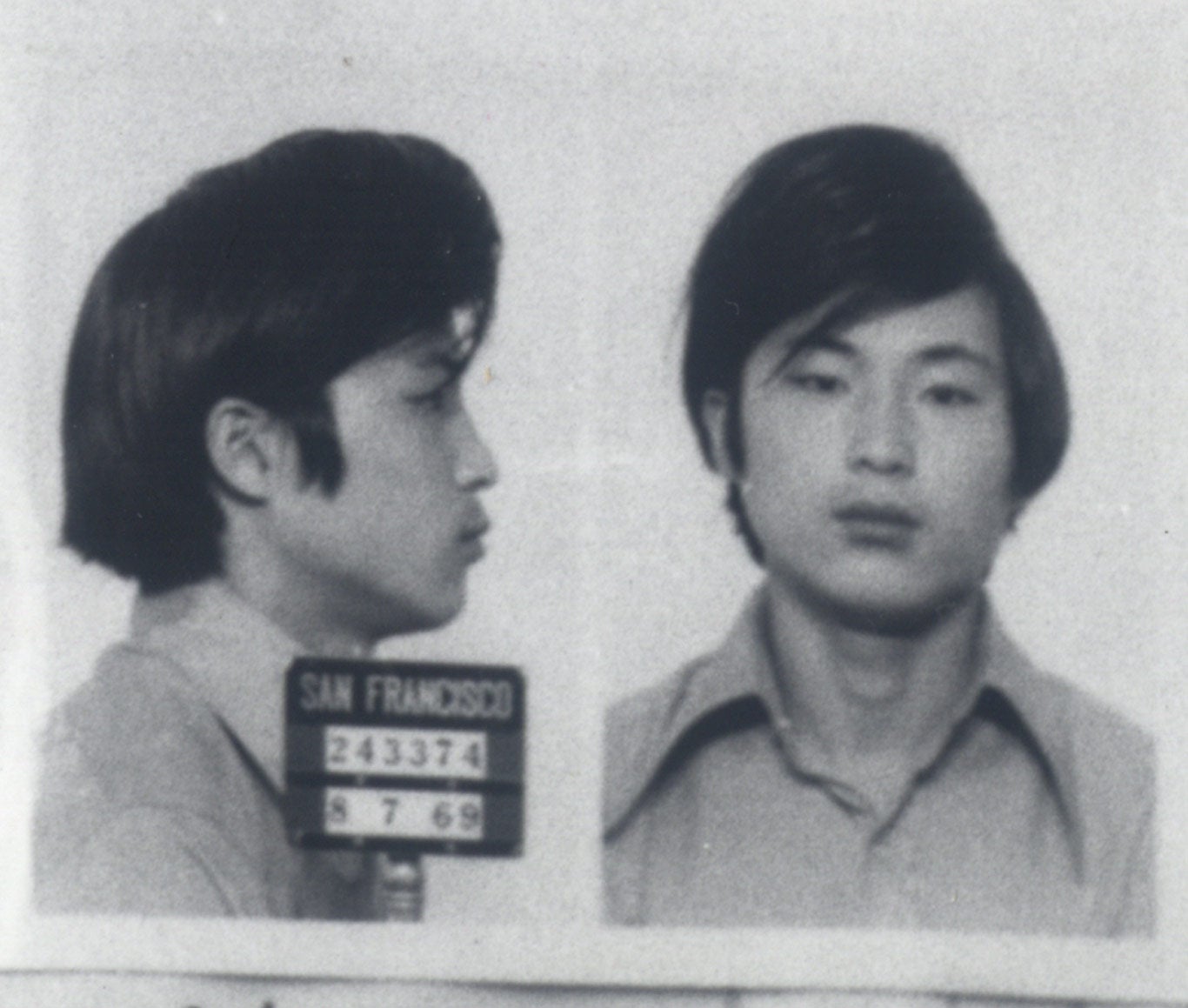

Image 44.02.04 — Chol Soo Lee in an undated childhood photo.

Courtesy of K.W. Lee. Metadata ↗

He was sent to an “Americanization” school to help him acclimate with other immigrants and language learners, but he was the only Korean in his school, which had predominantly Chinese American students. There were no bilingual Korean-speaking teachers, school staff, or peers to support him. One day, after a boy accused Chol Soo of starting a fight with him, Chol Soo was sent to the school office, where he grew agitated and allegedly kicked the vice principal. Police arrested a fourteen-year-old Chol Soo, and he was charged with battery. He was incarcerated in juvenile hall.

This marked his first brush with the criminal justice system and his entry into the “school-to-prison pipeline.” This term refers to the connection between damaging discipline policies at schools and youth entering the prison system. In recent decades, some schools have enforced “zero tolerance policies,” which place young people in a cycle of punishment and being treated as criminals. A 2005 study found that “children are far more likely to be arrested at school than they were a generation ago,” and the arrests are mostly linked to nonviolent offenses. Students who are racial minorities or have disabilities are most often the targets of this pipeline. 3

Chol Soo had only been in the country for two years before he was branded a criminal. This offense led to further institutionalization. One day, while in juvenile hall, authorities quoted him as saying, “I hate everybody and everybody hates me, and I want to die.” 4 So officials then sent him to a mental institution.

While at the McAuley Institute in San Francisco for three months, Chol Soo described being forced to take medications all day. Instead of receiving care and attention, he was heavily medicated. “There was nobody I could talk to,” he said. 5

Once released, Chol Soo frequently ran away from home and tried to survive on the streets. He would sleep in cars and burn tires to stay warm. One day he walked all the way to the Pacific Ocean, peered out at the water, and dreamt of returning to his family in Korea. He felt guilty for not sending them food packages during their time of need. He wondered why his mother brought him to America.

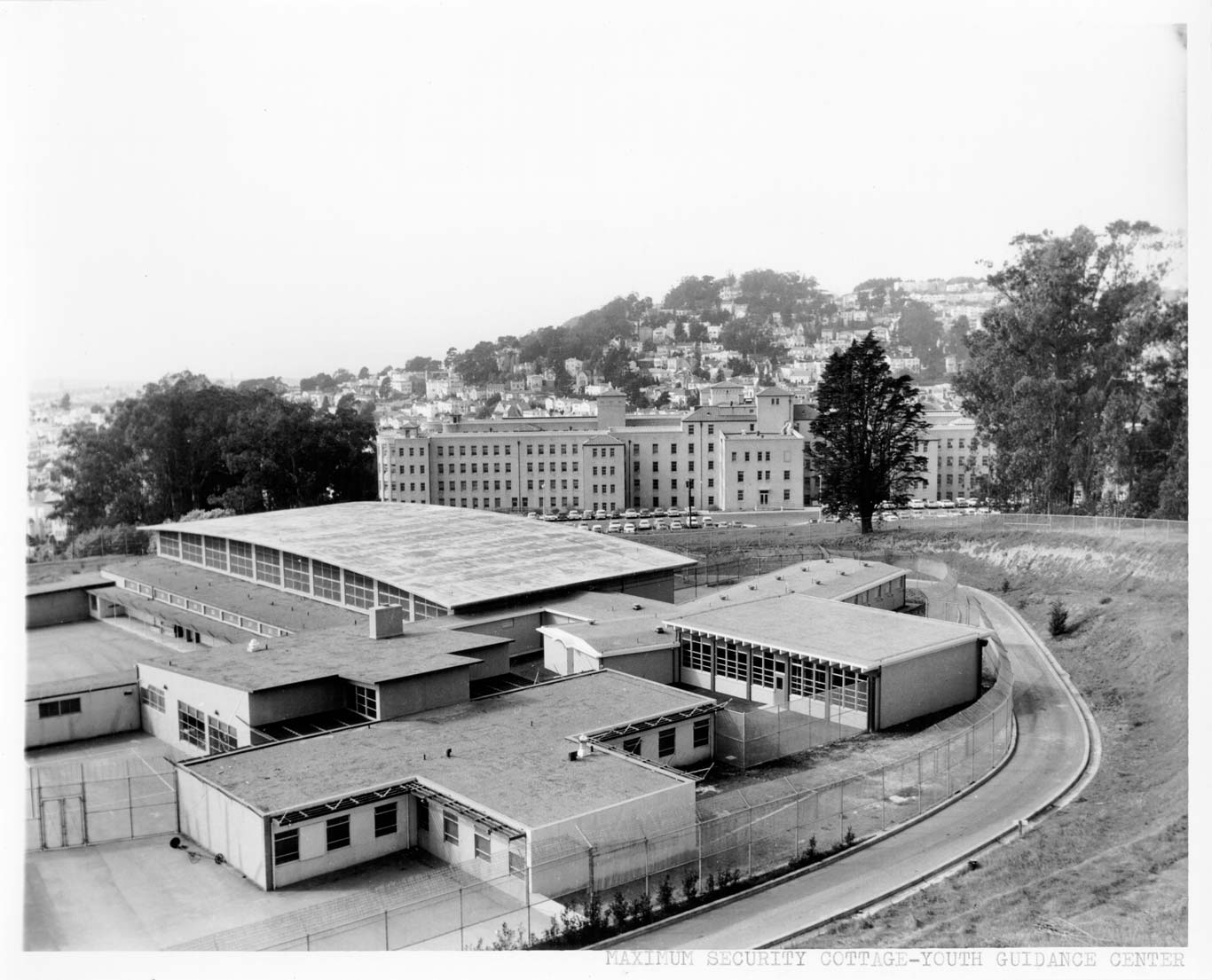

Image 44.02.05 — Chol Soo Lee spent some of his teen years in juvenile hall in San Francisco, including at a maximum security cottage like this one.

Courtesy of San Francisco Historical Photograph Collection. Metadata ↗

Systemic Isolation

Chol Soo Lee had many experiences of isolation in his life. After being separated from his mother, then his aunt’s family, he arrived in the US with little knowledge of English. He was bullied and penalized at school, and also abused at home. His school placed him in a cycle of punishment. Instead of trying to understand why he acted out violently with the vice principal, or even disciplining him within the school, school officials called the police.

That’s how he ended up in juvenile hall. From juvenile hall, he went to a mental health facility. His school, juvenile hall, and the mental health facility treated him as a problem instead of trying to understand his needs or helping him in a language he could understand. This further separated him from society.

Later in his life, Chol Soo realized how traumatic it was for him to leave Korea. He lamented how he did not encounter a single Korean-speaking counselor, teacher, interpreter, or lawyer as he navigated first the school, then the criminal justice system. Over time, he lost ties with the only family he ever knew—and lost his ability to speak Korean. While he was incarcerated for the Chinatown murder, his aunt’s family immigrated to the US and visited him in prison. He was unable to speak Korean, and they were unable to speak English, so they sat quietly, looking at each other. He wanted to call his aunt and uncle “mom” and “dad,” but stopped himself because his biological mother was at the visit. He watched as his cousin Myung-hak called him “hyeong” (meaning older brother in Korean) with tears streaming down his face.6

“I felt I had become a lost son and brother to the family who raised me,” said Chol Soo. “I returned to my cell and stayed there in a state of depression. I feel sadness about this even to this day. There is a word in Korean, oet’ori, which translates into English as ‘alone person’ or ‘outsider.’ I felt that I was one of those oet’oris of this world.” 7

Although Chol Soo’s experiences of family trauma and institutionalization happened more than fifty years ago, similar realities still exist for many Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in prison. In a 2019–2021 study, the Asian Prisoner Support Committee (APSC) surveyed incarcerated Asian American and Pacific Islanders in California, and the majority reported that they came to the US because of war in their home countries.

And like Chol Soo, many experienced the classroom as another traumatic environment. “Once settled in the United States, common experiences included racism, economic hardship, physical and emotional violence, and bullying in school,” stated the APSC report. 8 “Many respondents reacted to these forms of trauma by joining a gang.” Gangs offered protection, a social network, and a sense of belonging that wider society did not.

For Chol Soo, the way society viewed him — as a criminal — even began to affect how he saw himself. He said he learned to smoke cigarettes and act tough while in juvenile hall. He started to tell himself that he was a bad person. This was reinforced by his understanding of Korean culture. “This made sense according to my cultural upbringing in Korea,” he wrote, “in which problems with law enforcement made you a bad person.” 9

His own mother sadly reinforced this feeling, often beating her son. Carrying her own traumas, she had been banished by her own family in Korea for having Chol Soo out of wedlock and had herself been the victim of violence. A struggling, illiterate single mom, with no support in her adopted country, she likely felt isolated in the US as well.

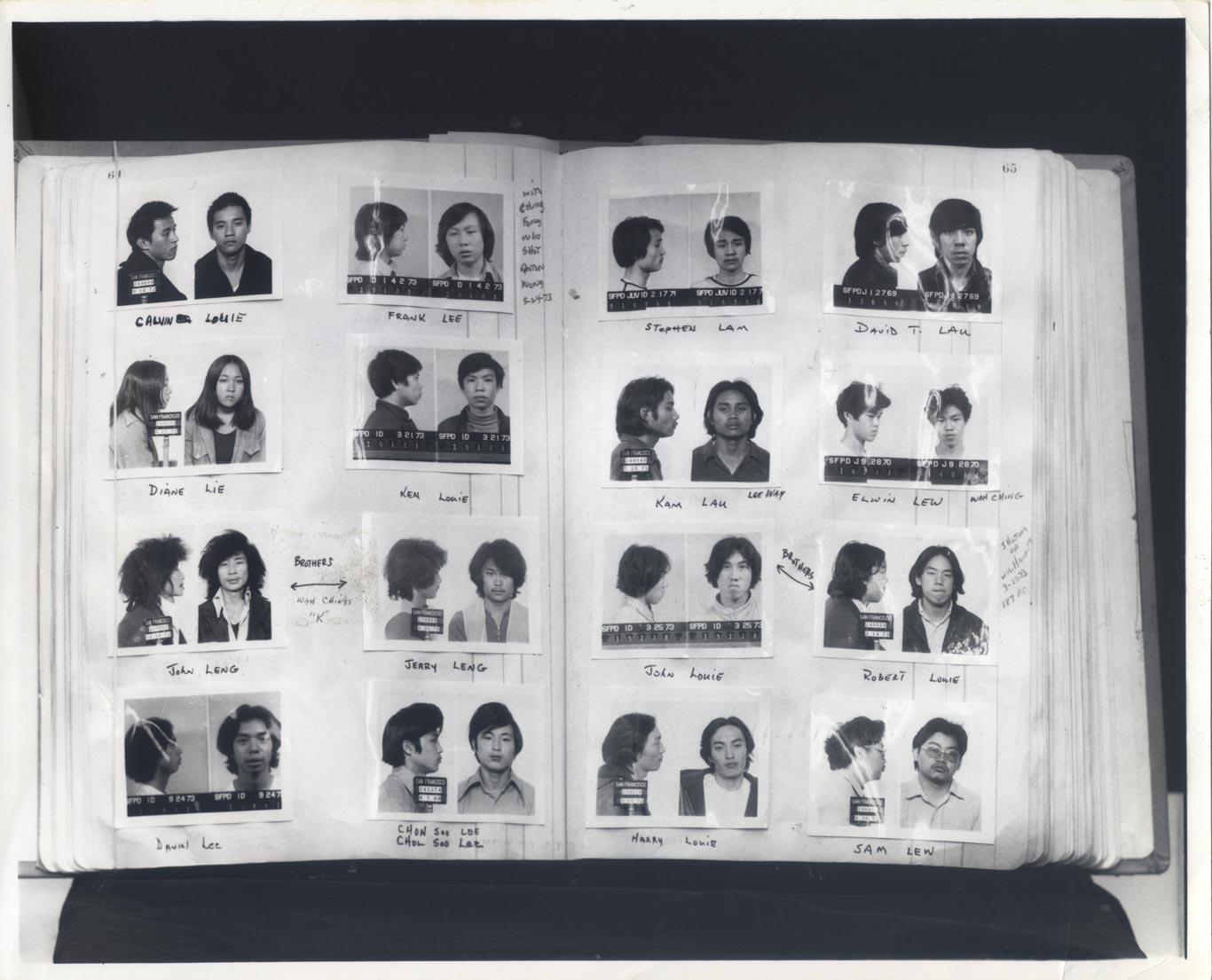

As a teen, Chol Soo often ran away to escape his mother’s violence. Police picked him up again and again and sent him to foster homes and California Youth Authority facilities. Several years later, his teenage mugshot would be one that witnesses to the Yip Yee Tak murder would pick out of a police mug book.

In just eight years in the US, Chol Soo went from a young person hoping to provide for his family in Korea to a convicted murderer fighting to survive in one of California’s most violent prisons.

Glossary terms in this module

school-to-prison pipeline Where it’s used

A term that refers to the policies and practices that push youth out of classrooms and into the prison system. Damaging discipline policies, such as zero tolerance policies and having police on school campuses, criminalize youth and discourage them from education.

Endnotes

1 Chol Soo Lee, “Thinking of Home,” unpublished, 1980, Private Collection of K. W. Lee.

2 Chol Soo Lee, Freedom Without Justice: The Prison Memoirs of Chol Soo Lee (University of Hawai’i Press, 2017), 97.

3 Marilyn Elias, “The School-to-Prison Pipeline,” SPLC Learning for Justice, Spring 2013, https://www.learningforjustice.org/magazine/spring-2013/the-school-to-prison-pipeline.

4 K.W. Lee, “Lost in a Strange Culture,” Sacramento Union, January 29, 1978.

5 K.W. Lee, “Lost in a Strange Culture.”

6 Lee, Freedom Without Justice, 134.

7 Lee, Freedom Without Justice, 134.

8 Asian Prisoner Support Committee, “Data Report on Incarcerated and Formerly Incarcerated AAPIs” (2019-2021), https://www.asianprisonersupport.com/apsc-survey-data.

9 Chol Soo Lee, Freedom Without Justice: The Prison Memoirs of Chol Soo Lee ( University of Hawai’i Press, 2017), 103.