Module 3: It Takes One Person

How does the life of Chol Soo Lee teach us about the roles each of us can play in creating a more just society?

In many ways, the movement to free Chol Soo Lee started with a single spark: a college student named Ranko Yamada. Along with her sister Reiko, who worked at a pearl store in Chinatown, Yamada met Chol Soo about a year before his arrest. Knowing the nineteen-year-old Chol Soo to be a loner, they would sometimes invite him out to dinner. “We had developed a friendship of respect and trust,” Yamada said. “He had always been honest with Reiko and me.” 1

It was this friendship, plus her own strong sense of humanity and justice, that drove Yamada to become a fierce advocate for Chol Soo after he was charged with murder. Her early efforts would make a profound impression on journalist K. W. Lee, who brought Chol Soo’s story to a national audience.

This module traces the seeds of the Free Chol Soo Lee movement to the actions of activist Ranko Yamada and journalist K. W. Lee. We will learn how their courage and commitment laid the groundwork for a grassroots pan-Asian American movement.

Who is Ranko Yamada?

Who is K. W. Lee?

How did the Free Chol Soo Lee movement, as a grassroots social movement, begin?

Ranko Yamada

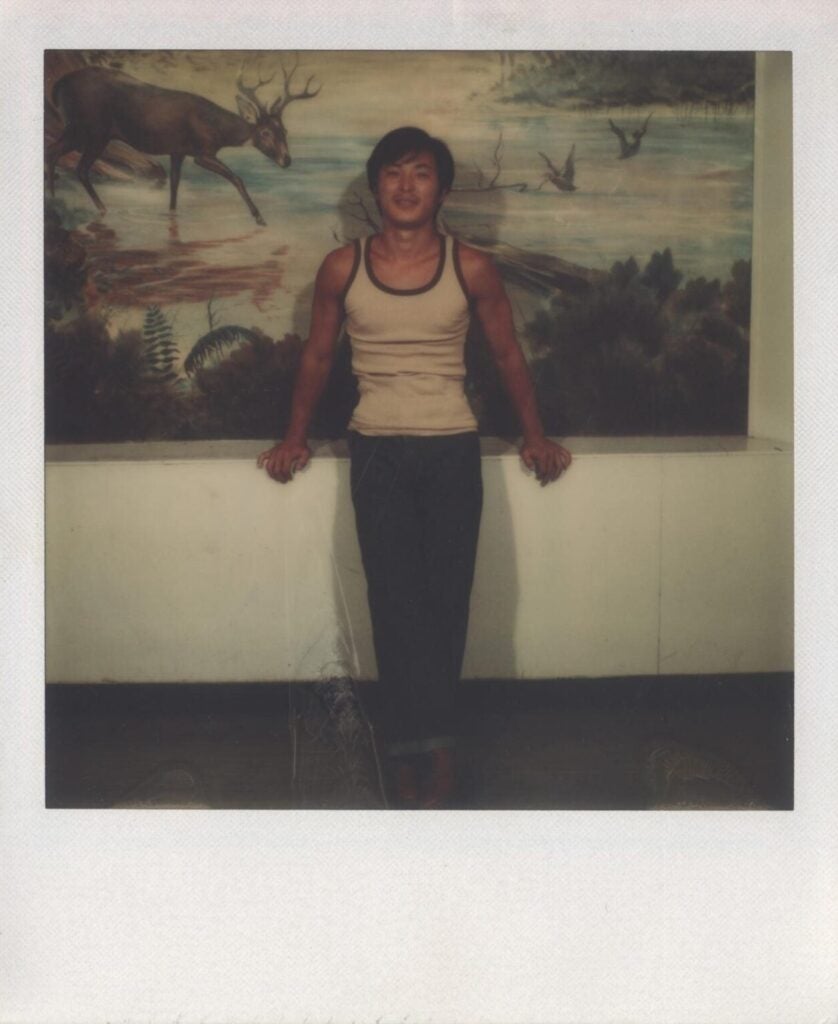

Chol Soo Lee, who described himself as a “young street punk” living in Chinatown in the early 1970s, was on probation for theft at the time he met the Yamada sisters. But that did not cause them to shy away from him. In fact, Chol Soo once asked Ranko Yamada to accompany him to a meeting with his probation officer. He thought the presence of “this nice Japanese girl” 2 might help the officer think better of him.

Image 44.03.01 — Chol Soo Lee, in a 1970s Polaroid.

Courtesy of Ranko Yamada. Metadata ↗

The following summer, Yamada knew something was amiss when she read in the newspaper that Chol Soo was arrested for the murder of a Chinatown gang leader. She did not believe he was capable of such a crime. Moreover, she knew from her friends in Chinatown that it was unlikely Chol Soo was in any Chinatown gang. Locals knew him as “the Korean,” and most Chinatown gang members were Chinese. 3

However, Yamada was also familiar with the weaknesses of the criminal justice system. She feared that the truth might not matter to San Francisco police, who at the time, she said, “had been out in full force … in Chinatown, both uniformed and undercover, stopping and detaining people just because they were young and Asian.” 4 This type of targeting is called racial profiling.

Even though she did not have a close friendship with Chol Soo at the time of his arrest for murder, Yamada knew she needed to act. She believed the criminal justice system would not necessarily recognize its wrongful arrest and correct its error. “The situation demanded that people not allow this kind of thing to happen,” she said. “It demanded people to act and confront it.” 5 Ranko made the decision she would be one of those people.

Image 44.03.02 — Ranko Yamada, in the newsroom of the Koreatown Weekly, 1979. Yamada befriended Chol Soo Lee about a year before his 1973 arrest for the Chinatown murder, and would become a leading figure in the movement to free him from prison.

Courtesy of K.W. Lee. Metadata ↗

She began raising money for a defense attorney. She asked one hundred people for $10 cash donations, hawked her own jewelry, and organized campus fundraisers. But her efforts failed to earn enough. She was turned down by ten attorneys. “These lawyers had been described as excellent and progressive,” said Yamada. “I was so naïve. I expected someone to take the case on good faith alone.” 6

Yamada knew how alone Chol Soo was, and how much he needed help. In her teens, she had been the victim of a violent crime and nearly lost her life. Unlike Chol Soo, she received an outpouring of support from family, friends, and community, which helped heal her. This experience changed her perspective on life. “Suddenly the life you live is a freebie,” she said, “and you are able to act more freely on things you think may be important.” 7

Helping Chol Soo was not only the right thing to do, in her mind, but also important for Yamada on a personal level. “If I knew that he had a support system in place for his defense, I would not have done anything,” she said. “But he didn’t have anything. And I just felt like … I had this horrible secret. I knew that he needed help, he wasn’t going to get it, and something so terribly wrong was going to happen.” 8

Her fears were realized on June 19, 1974, when Chol Soo was convicted of first-degree murder. He was sentenced to life in prison.

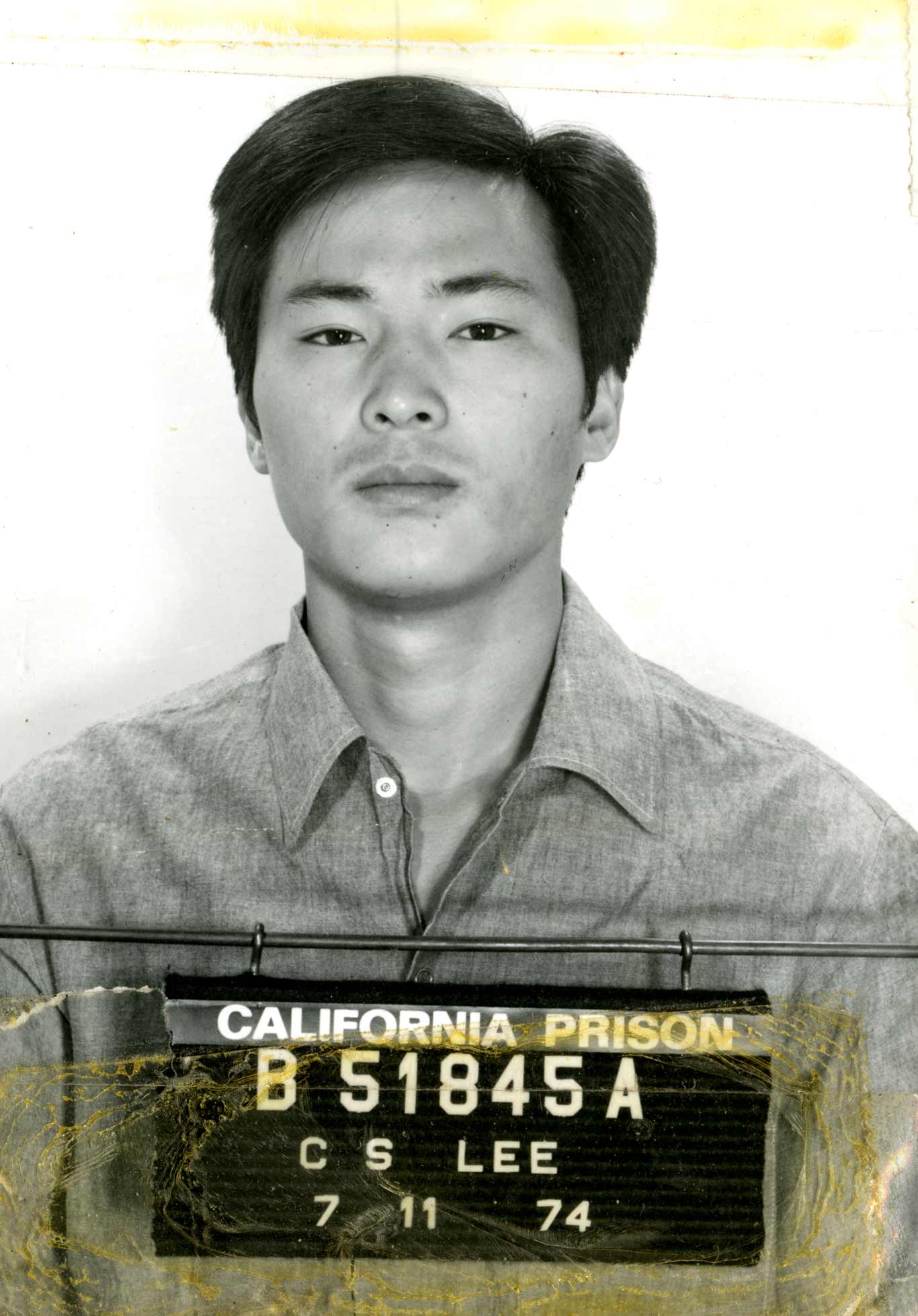

Image 44.03.03 — Chol Soo Lee’s 1974 prison mugshot.

Courtesy of California State Archives. Metadata ↗

At that point, Yamada vowed to become an attorney—the type who would take on a case like this one. A student at the University of California, Santa Cruz, she charted her path to law school. In the meantime, she supported Chol Soo as a friend, writing letters and sending books and care packages. These gestures proved a crucial lifeline for the isolated Chol Soo, whose own mother wavered in her support.

“My angry cry for justice was heard only by Ranko,” said Chol Soo. Although these early efforts would not win his freedom, he described her friendship as “pure light in my darkened world.” 9

K.W. Lee

Chol Soo Lee was not aware that there was another person who believed in his innocence. Tom Kim, a Korean American social worker in the Bay Area, had crossed paths with Chol Soo only a handful of times in Chinatown, but he felt strongly that the young man was not capable of murder.

At a gathering in Davis, California in 1977, Kim met K. W. Lee, the chief investigative reporter for the Sacramento Union. When Kim mentioned Chol Soo’s case, K. W. thought of his nephew, who had the same name. His nephew was working as a scientist in Ohio, while this other Chol Soo Lee was fighting for survival in a California prison. He thought about the “thin line” between one Korean immigrant’s American dream and the other’s nightmare. 10 He knew he had to investigate the case.

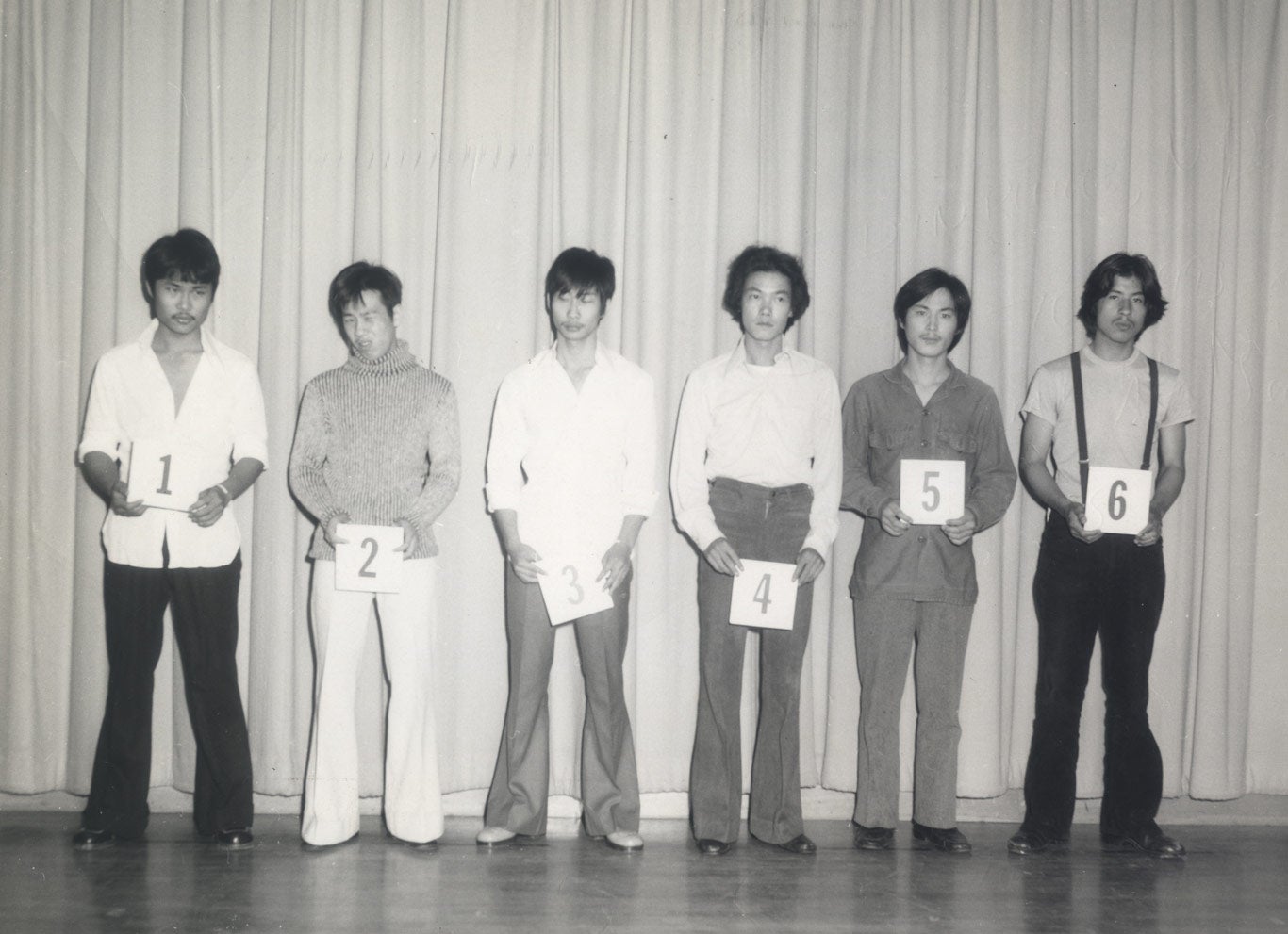

Image 44.03.04 — Chol Soo Lee is no. 5 in this 1973 San Francisco Police Department lineup photo.

Courtesy of Josiah “Tink” Thompson/Free Chol Soo Lee Film. Metadata ↗

Over six months, K. W. “followed the smell,” as he put it, 11 carefully examining police and court records on the Chol Soo Lee case. He also made frequent visits to San Francisco’s Chinatown to visit the crime scene and interview sources. He exposed alarming findings in the police investigation and prosecution of Chol Soo:

- The weapons evidence was invalid. Police initially focused on Chol Soo because a ballistics test determined the murder weapon matched a bullet he had accidentally fired into the wall of his room. That test was ruled erroneous before his murder trial, but authorities still pushed ahead with Chol Soo’s conviction.

- Chol Soo did not match the description of the killer. While eyewitness accounts put the culprit as tall as 5-foot-10, Chol Soo stood no taller than 5-foot-4. Chol Soo also had a mustache, a facial feature not a single witness mentioned.

- The police used questionable tactics with witnesses. Although witnesses selected several mugshots of Asian males, including Chol Soo’s, only Chol Soo was put in the live lineup. This may have steered witnesses to pick Chol Soo. Three of the six witnesses, all white, identified Chol Soo.

- The police did not understand Chinatown gangs. The San Francisco police thought the Chinatown gang called the Wah Ching hired Chol Soo to be an executioner. However, multiple sources in Chinatown told K. W. that a Chinese gang would not hire a Korean person for such a killing.

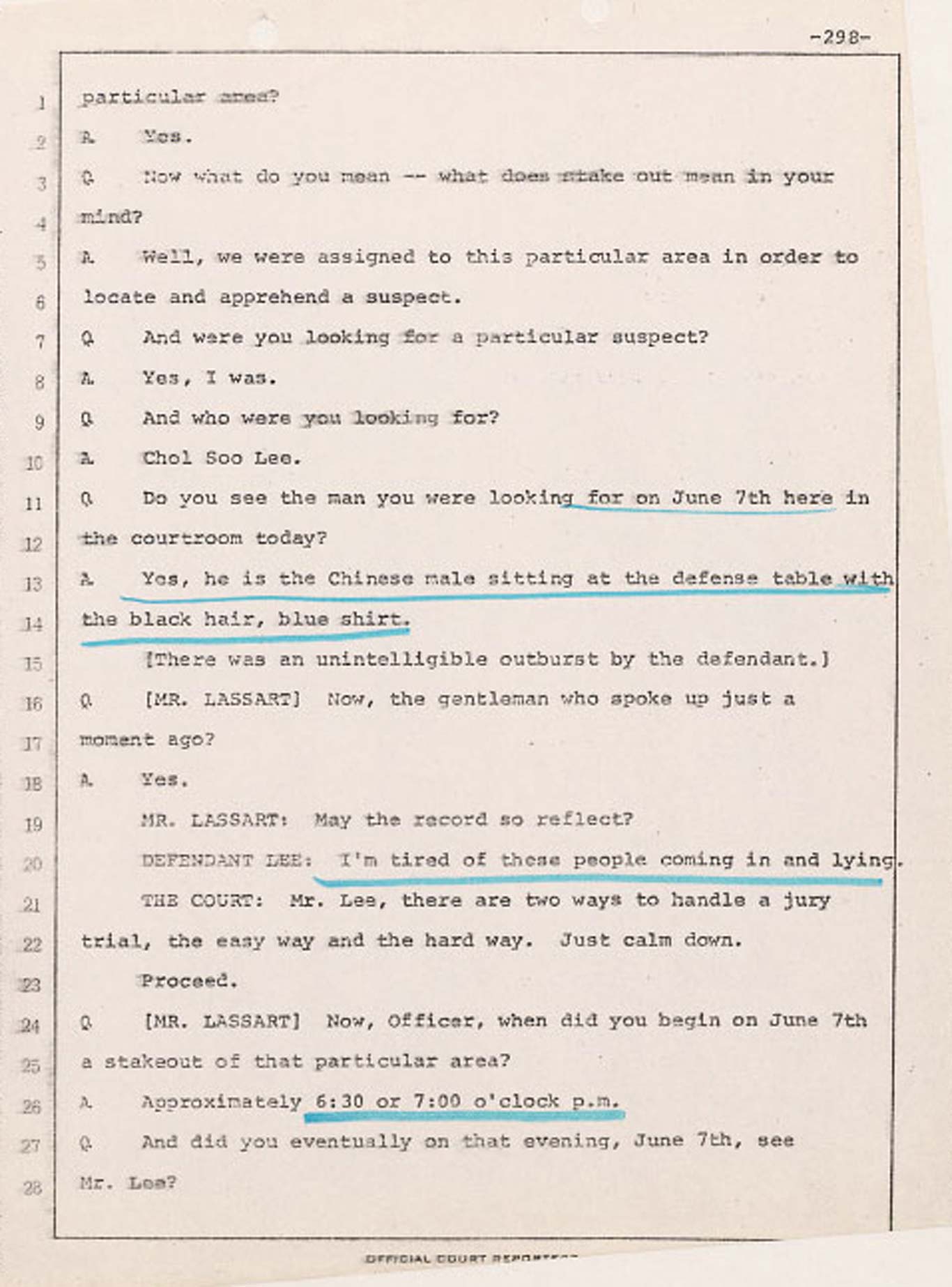

- Police officers and the court ignored Chol Soo’s Korean ethnicity. Transcripts from the murder trial revealed how the arresting officer pointed at Chol Soo from the witness stand and called him “the Chinese male.” His court-appointed defense attorney never objected. There was only an “unintelligible outburst” by the defendant that was noted by the court reporter. 12

Text 44.03.05 — K. W. Lee marked up this transcript of the 1974 trial of the People of the State of California vs. Chol Soo Lee. The underlined parts reveal how the police officer who arrested Chol Soo Lee misidentified him as “Chinese,” and Chol Soo’s reaction.

Courtesy of K.W. Lee Papers, UC Davis Shields Library. Metadata ↗

As K. W. continued to discover major errors in the handling of Chol Soo’s case, he was shocked to read a news brief that Chol Soo had gotten into a violent altercation with another inmate in the prison yard. Chol Soo had killed Morrison Needham, a member of the Aryan Brotherhood prison gang, in what he said was self-defense. But authorities charged him with murder. Because this was his second murder charge, it was now a death penalty case. The journalist urgently needed to meet Chol Soo.

“My name is Kyung Won Lee,” he began his letter. “I am a Korean who came to America in 1950 … and have been working as a newspaper man since 1957. I want to write about the problems you have run into as a bewildered and helpless Korean boy in America. Maybe … society will listen.” 13

Chol Soo seemed to be both surprised and comforted that, finally, someone believed in his innocence and saw his humanity. “I too am human being and like other people I want to see my life worthwhile to live and enjoy,” he wrote. “But to be frame[d] for murder I didnt [sic] commit, the courts has place for me to live like dead person in living body.” 14

Upon meeting behind prison walls, K. W. said he felt a deep connection to Chol Soo, as a fellow Korean immigrant who sometimes felt alone himself in his adopted country.

He strongly related to Chol Soo’s story and understood how his own life could have mirrored Chol Soo’s. “It was just by the grace of God I have eluded the fate that fell on him,” he reflected. “Because there’s a very thin line between him and me … I was lucky. He was not lucky. And there are an awful lot of unlucky people. Especially Asians, because they have no language … they couldn’t tell their story. That’s why Asian American journalists have a moral obligation to tell their story.” 15

The award-winning reporter had spent his career writing about the struggles of poor white working-class families in West Virginia and other racial minorities in the Jim Crow South and California, but this was the first time he would be writing about an immigrant from his shared motherland.

But first, K. W. had to convince his Sacramento-based newspaper to cover a story about a murder in San Francisco. He made a deal with his editor, who agreed that the reporter could investigate the Chol Soo Lee case so long as he did so on his own time and found enough evidence to suggest Chol Soo was innocent.

Even though K. W., a married father of three, privately harbored doubts about committing himself to such a demanding case, he could not turn away. Chol Soo urged K. W. to reach out to Ranko Yamada for assistance.

When K. W. met Yamada, she cleared away any uncertainty he felt about his commitment. Despite it being finals week, the law student drove from San Francisco to Sacramento in the pouring rain to see him. Yamada brought along a bundle of elaborate notes on Chol Soo’s case. K. W. was moved by this young Japanese American woman’s four-years-long dedication to the plight of a “faceless Korean immigrant street kid.” 16

“It takes one person … not a president, not a star, not a whole village, it takes one humble person to start a movement,” he would later reflect. “It takes one person who inspires another, then another.” 17 And that person, he said, was Ranko Yamada.

Image 44.03.07 — Ranko Yamada (standing), with other activists, including Mona Litrownik (seated in red T-shirt) in San Francisco in 1978. There are educational pamphlets on the table, and they are selling hot links and T-shirts to fundraise for Chol Soo Lee’s legal defense fund.

Courtesy of Ranko Yamada. Metadata ↗

The Articles

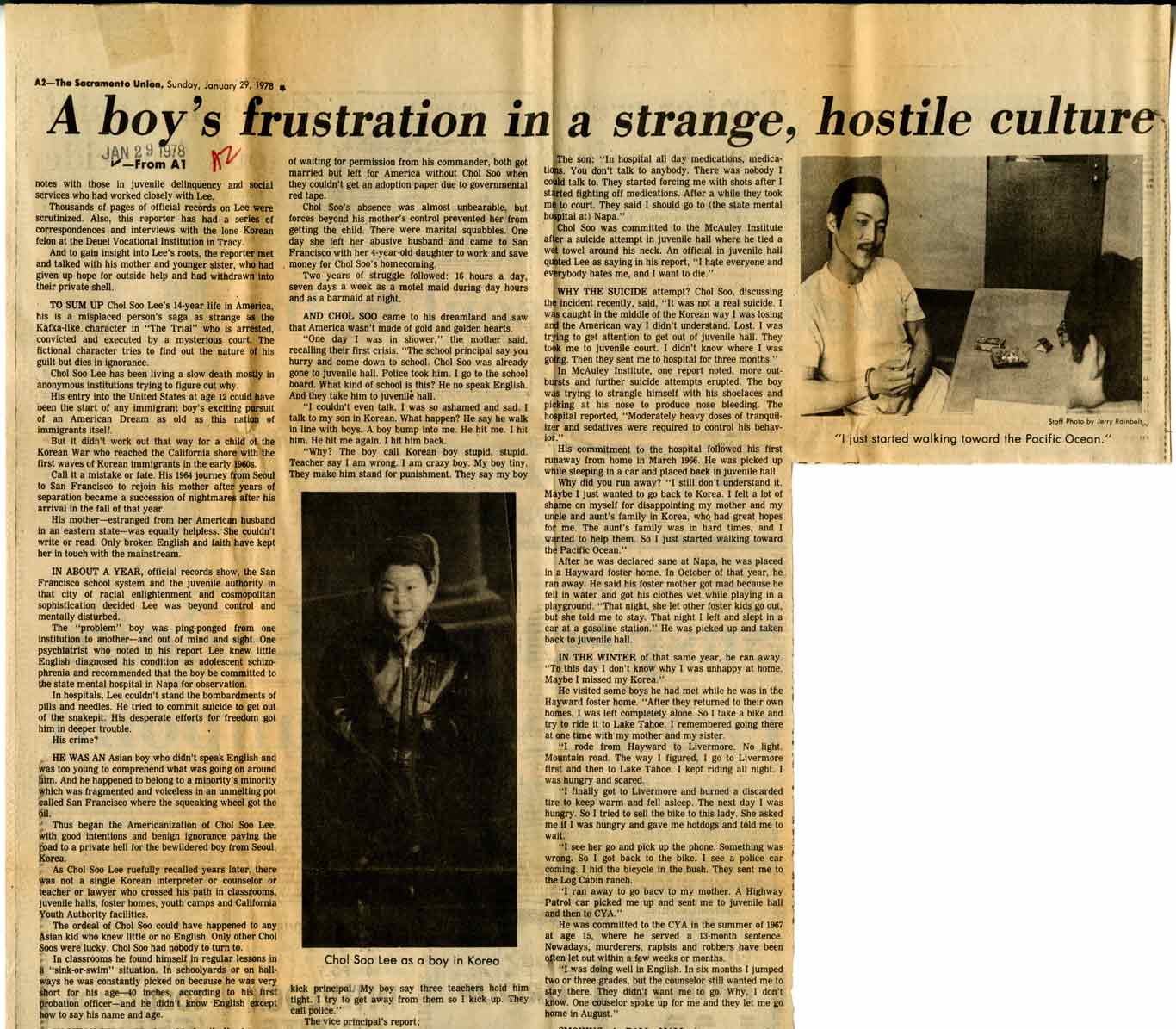

K. W. Lee’s investigation resulted in a two-part series published on January 29 and 30 of 1978. The articles not only exposed holes in the conviction of Chol Soo Lee, but also treated Chol Soo as a human being—something that others had failed to do during the young man’s time in school and prison.

The reporter described Chol Soo’s traumatic time in the US. “His entry into the United States at age 12 could have been the start of any immigrant boy’s exciting pursuit of an American Dream,” he wrote in his first article “Lost in a Strange Culture.” “But it didn’t work out that way for a child of the Korean War … His 1964 journey from Seoul to San Francisco to rejoin his mother after years of separation became a succession of nightmares.” 18

Text 44.03.08 — In this January 29, 1978, article, published in the Sacramento Union, K. W. Lee describes the isolating and traumatic experiences Chol Soo Lee endured in America.

Courtesy of Sacramento Union Archive, UC Davis Shields Library. Metadata ↗

Chol Soo had only been in the US for about eight years when he was accused of the Chinatown murder. His first public defender did little to help, failing to locate witnesses to corroborate his alibi that he was nowhere near the crime scene. Within a year, Chol Soo was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to life in one of California’s most violent prisons.

K. W. concluded that Chol Soo was caught up in an “ethnocentric system oblivious to and ignorant of the realities and experiences of Asian ethnic groups in California.” As evidenced at Chol Soo’s murder trial, the police, and even his own defense attorney, did not distinguish between Chinese and Korean. “Long isolated and removed from the fragmented Korean community, Lee has maintained his innocence,” wrote K. W. about Chol Soo Lee. “Few have listened to his muffled cry for justice.” 19

But that was all about to change. The moral conviction and courage displayed by Ranko Yamada and K. W. Lee laid the groundwork for a pan-Asian American grassroots movement, with each participant inspiring the next.

Glossary terms in this module

alibi Where it’s used

A claim or piece of evidence that shows a person was somewhere else at the time of a crime and proves their innocence.

grassroots Where it’s used

A term used to describe a movement or organization that starts with everyday people, instead of people in positions of power.

racial profiling Where it’s used

The unconstitutional practice of law enforcement officials who target, harass, and discriminate against individuals for suspicion of crime based on their race, ethnicity, religion, or nationality.

Endnotes

1 Ranko Yamada, Koreatown Weekly, December 17, 1979, 8.

2 Ranko Yamada, interview for Free Chol Soo Lee, July 16, 2017.

3 Yamada, Koreatown Weekly, 8.

4 Yamada, Koreatown Weekly, 8.

5 Yamada, Koreatown Weekly, 8.

6 Ranko Yamada, “Personal Thoughts,“ Amerasia Journal 39, no.3 (2013): 31.

7 Ranko Yamada, interview for Free Chol Soo Lee, July 16, 2017.

8 Ranko Yamada, interview for Free Chol Soo Lee, March 17, 2016.

9 Chol Soo Lee, Freedom Without Justice: The Prison Memoirs of Chol Soo Lee (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2017), 121.

10 K.W. Lee, “Untitled K.W. Lee Community Tribute,” interview by Sandra Gin, 1994.

11 Chol Soo Lee, “A Question of Justice.”

12 Lee, “Alice-in-Chinatown Murder Case,” A5.

13 K. W. Lee, written correspondence, Nov. 22, 1977.

14 Chol Soo Lee, written correspondence, Nov. 27, 1977.

15 K. W. Lee, interview, 1994.

16 K.W. Lee, Koreatown Weekly, December 17, 1979, 2.

17 K.W. Lee, remarks at Chol Soo Lee Symposium, University of California, Los Angeles, December 7, 2013.

18 Lee, “Lost in a Strange Culture.”

19 Lee, “Alice-in-Chinatown Murder Case,” A5.