Module 4: ‘Blue Jeans and Chima Jeogori Getting Together’

How does the life of Chol Soo Lee teach us about the roles each of us can play in creating a more just society?

After journalist K. W. Lee published a two-part series about Chol Soo Lee’s life and murder conviction in the Sacramento Union, people took notice. A small group of socially conscious first-generation Korean Americans in the Sacramento, California, area formed the Chol Soo Lee Defense Committee. As news of the case spread, young Asian Americans also mobilized. Together, they built a pan-Asian, multigenerational grassroots social movement to free Chol Soo. For six years, these disparate groups—young and old, immigrant and US-born, conservative and progressive—united in common cause to help a stranger.

Image 44.04.01 — Young activists, pictured here at a late 1970s protest, formed the backbone of the Free Chol Soo Lee movement.

Courtesy of Ken Yamada, Unity Archive Project. Metadata ↗

Why did Chol Soo Lee’s story resonate with other Korean immigrants?

In what ways did the younger members of the Free Chol Soo Lee movement try to raise awareness and funds for his defense?

How did the support of the Asian American community affect Chol Soo Lee’s case, especially in the courtroom?

Chol Soo Lee Defense Committee

After learning about Chol Soo Lee’s case, Jay Kun Yoo, a University of California, Davis, law school graduate, and Grace Kim, a Davis-based educator and activist, started the Chol Soo Lee Defense Committee. Their goal was to educate the public about Chol Soo’s case, gain community support, and raise funds for his legal defense.

Because of their strong Christian ties, Yoo and Kim started their education and fundraising efforts in Korean churches. Congregants related to Chol Soo’s “American-dream-turned-nightmare” story. They also found significance in Chol Soo’s birthdate, August 15, 1952, which marked the anniversary of Korean Independence Day and was in the middle of the Korean War. “Chol Soo” was a popular name in Korea at the time. The prisoner came to symbolize someone who carried “all the sad history of Korea,” said Yoo. 1

A church elder himself, Yoo passionately urged congregants to help free Chol Soo, who had been suffering alone for much of his life. He urged them to think of Chol Soo’s future: “He could come out and become a pastor, or a famous criminal defense attorney or a young leader, to make great contributions to help other Koreans and Asians immigrants in America, and minority groups in America as well, so that they won’t be ignored.” Yoo would tell them, “‘My fellow Koreans, we must help Chol Soo.’” 2 Such church pleas were often met with tears, he said, followed by personal donations to support Chol Soo’s cause.

Image 44.04.02 — Jay Kun Yoo speaks to the crowd of supporters at a courthouse demonstration during Chol Soo Lee’s murder retrial in San Francisco in 1982.

Courtesy of Ken Yamada, Unity Archive Project. Metadata ↗

Asian America

But it wasn’t just Korean immigrants who identified with Chol Soo Lee. His story resonated with young second-, third- and fourth-generation Japanese, Chinese, and Korean American social workers, educators, activists, and college students. Many of them were already feeling empowered and inspired by other movements of that period, including the Black Power, ethnic studies (also known at the time as the Third World Liberation Front), civil rights, and antiwar (anti-Vietnam War) movements.

Ranko Yamada said K. W. Lee’s articles moved people to action for two reasons: the “genius in his writing” that made a complex case easier to understand, and the depth of his compassion for Chol Soo. The articles, Yamada said, made Chol Soo a real person. “And not just a real person that you read about, but somebody like in your own family – or ‘it could be me.’ He created the identity, the community consciousness of an identity for Chol Soo.” 3

“Asian American” was still a relatively new term by the time the Free Chol Soo Lee movement was born. In 1968 activists created the term “Asian American” as a political identity to bring together different Asian ethnic groups, such as Japanese, Chinese, and Filipinos, who made up the majority of Asians in America at the time.

The 1960s were a time of great social upheaval. The civil rights and the Black Power movements mobilized many Asians in the United States to learn about and act against systemic racism. They also felt empowered to embrace the idea of self-determination, instead of bowing down to societal norms that rendered them invisible in America.

“From the streets, the campuses, and even from middle-aged, middle-class urban enclaves throughout the United States, these self-defined Asian Americans linked destinies to defy white standards of truth and beauty, lay claim to our lost histories, and affirm ourselves as a political force,” 4 described Karen L. Ishizuka, author of Serve the People: Making Asian America in the Long Sixties.

These conditions seemed to set the stage for the creation of a pan-Asian American movement, with an entire cohort of young Asian Americans who became politicized by the cause.

Jeff Adachi, an undergraduate at University of California, Berkeley, was one of them. He said that he and his roommate David Kakishiba felt called to action after they ran across K. W. Lee’s “Alice in Chinatown” article about the Chol Soo Lee case.

For Adachi, Kakishiba, and many other young activists, this cause spoke to them on multiple levels. Adachi said: “It was sort of a perfect storm because you had a community that had not been mobilized before, you had a person who symbolized the injustice that existed in the criminal justice system in America, and you could talk about racism and all the larger issues while focusing on this one man’s case. And there was a clear goal – and that was to free Chol Soo Lee.” 5

Young people infused a new energy into the Free Chol Soo Lee movement. While older Korean immigrant leaders of the defense committee fundraised mainly at churches, the younger generations held car washes, dance parties, and sold hot links to raise money. Adachi wrote a poem that he and some Asian American musicians would turn into a protest song, “The Ballad of Chol Soo Lee,” which they recorded on a 45 rpm vinyl album.

Packing the Court

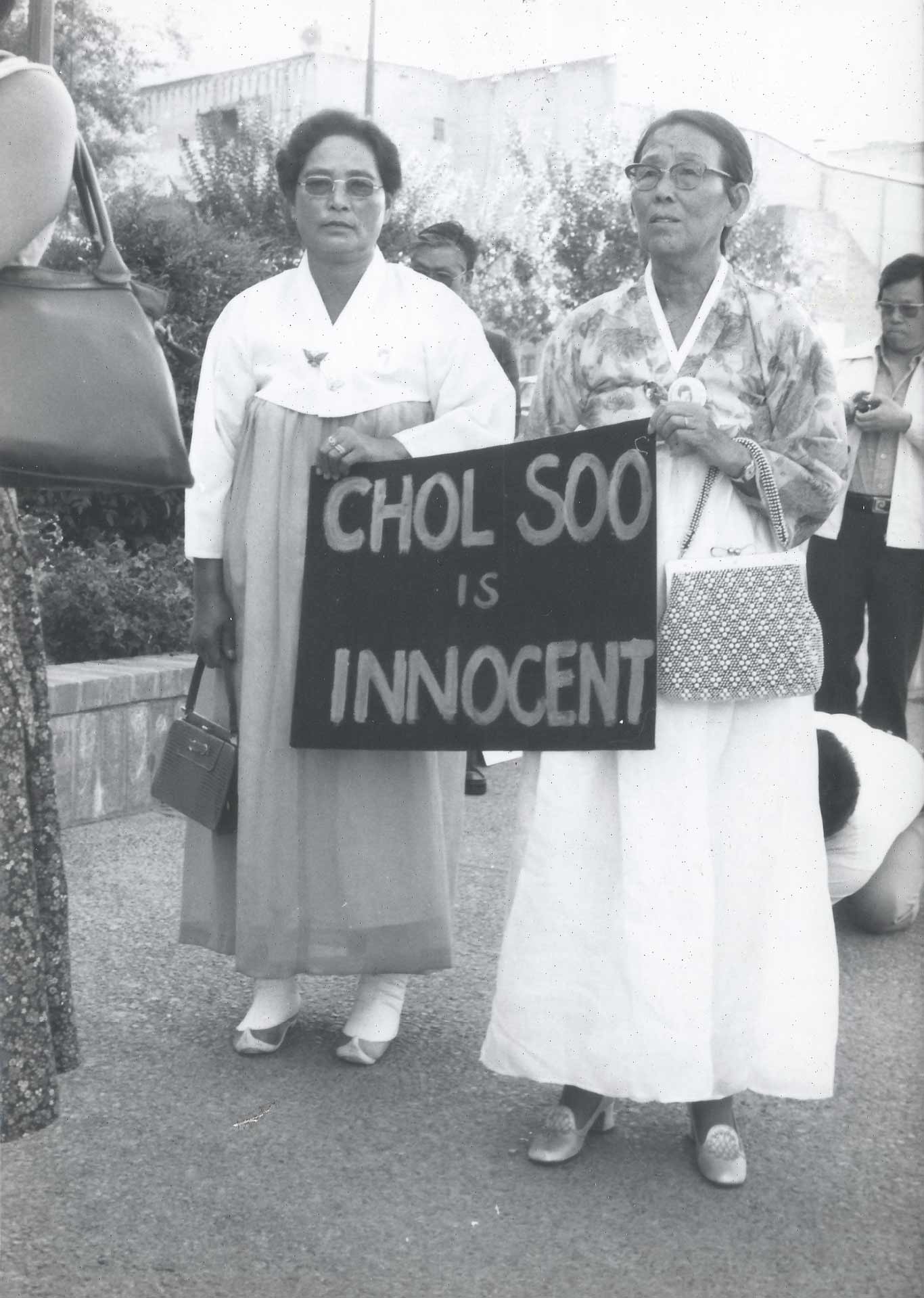

As Chol Soo Lee’s case traveled through the legal system, activists and supporters would pack the courtrooms. Immigrant Korean grandmothers, some of them wearing traditional silk dresses, were shoulder to shoulder with Asian American college students, who wore denim bell bottoms. Their protest signs were written in both English and Korean.

The scholar Richard Kim called the movement “an extraordinary coalition of people from a broad spectrum of social backgrounds.” It marked a “pivotal moment in Asian American history when the Asian American movement united around one of its first major political campaigns.” 6

Kim noted that there were vast political differences among members of this movement. Many of the young activists were “pretty radical in their politics,” he said. “Some of them were involved in communist movements, coming out of the 1960s social movements, and here they are working with these recent Korean immigrants, who were probably the most diehard anti-communists.” Activist Jay Kun Yoo described it as “blue jeans and chima jeogori (Korean traditional clothing) getting together.” 7

This bold and passionate fight for justice in his name deeply moved Chol Soo, who said, “Every day I would go to court and feel strong and refreshed that I was not on trial alone.” 8

Image 44.04.04 — Two women, dressed in Korean traditional dresses, take part in a courthouse protest in Stockton, circa late 1970s.

Courtesy of Gail Whang. Metadata ↗

The National Chol Soo Lee Defense Committee

The small defense committee that had formed in Sacramento eventually spread to San Francisco and Los Angeles, and from there, grew into a national movement, with committees in New York, Hawai‘i, Washington state, Georgia, and all across the country. Other mainstream media outlets, including the San Francisco Chronicle and Los Angeles Times, began to cover the Chol Soo Lee case. It was also closely followed by the Korean-language and Asian American ethnic press.

Warren Furutani, a longtime community and human rights activist who joined the Los Angeles defense committee, noted that the coverage by the Korean-language media had an impact on the movement. “Initially the case was barely reported for fear that any criticism of the [American] judicial system would place the Korean media in a bad light,” he said. “But as the support movement grew, so did the coverage.… Their participation was invaluable as they were a consistent source of updated information. They also publicized events and raised funds on behalf of Chol Soo.” 9

Thanks to these efforts, the defense committee raised enough money to hire nationally renowned defense attorneys and a private investigator. They tracked down new witnesses, including a man named Steven Morris who saw Yip Yee Tak’s killer from a distance closer than any other witness that had testified. Although the police knew about Morris, his existence was hidden from the defense for years. When he was finally called to the stand, he said definitively that Chol Soo was not the killer.

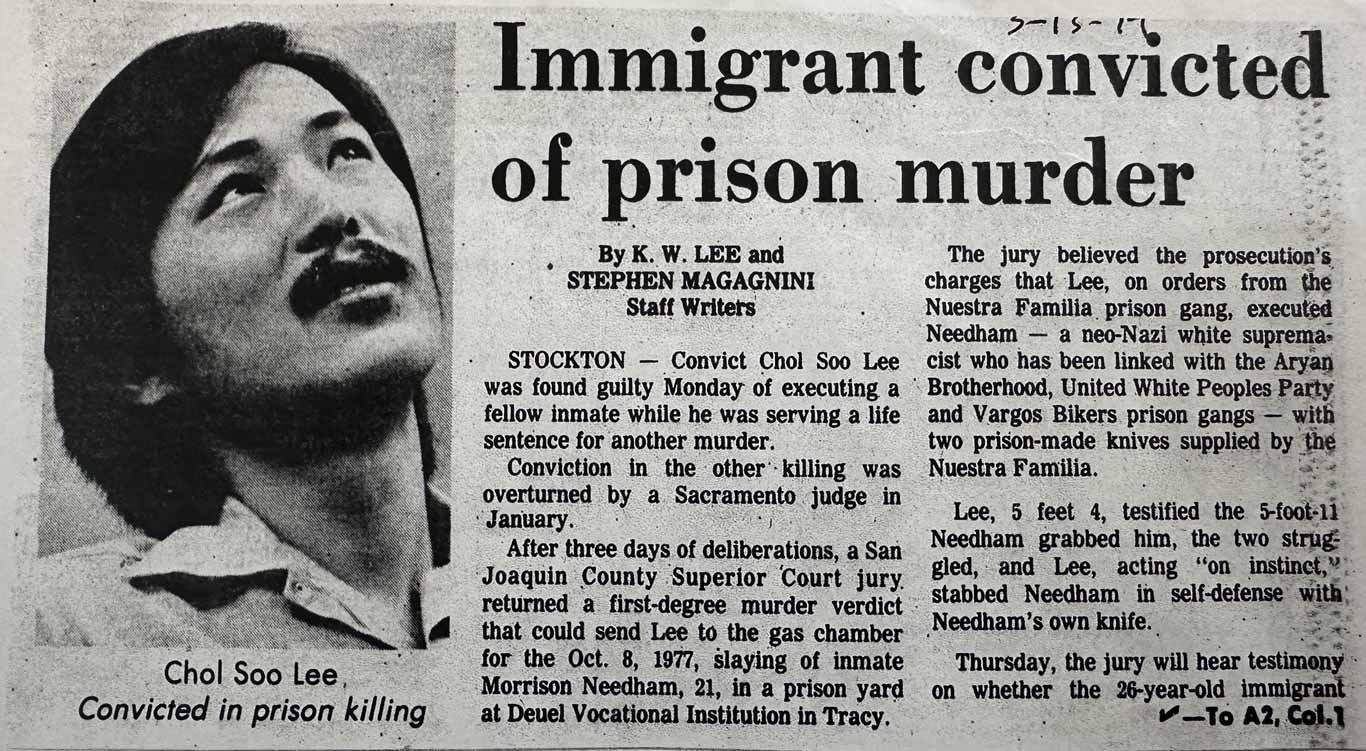

This testimony led to a Sacramento court overturning Chol Soo’s Chinatown murder conviction in 1979. But the challenges in the court system were not over. About a month after this victory, a Stockton jury would convict him of first-degree murder in the prison-yard case. Chol Soo was then sentenced to die in the prison gas chamber—devastating news that was met with his supporters chanting defiantly, “Freedom for Chol Soo Lee!” in the courthouse corridors.

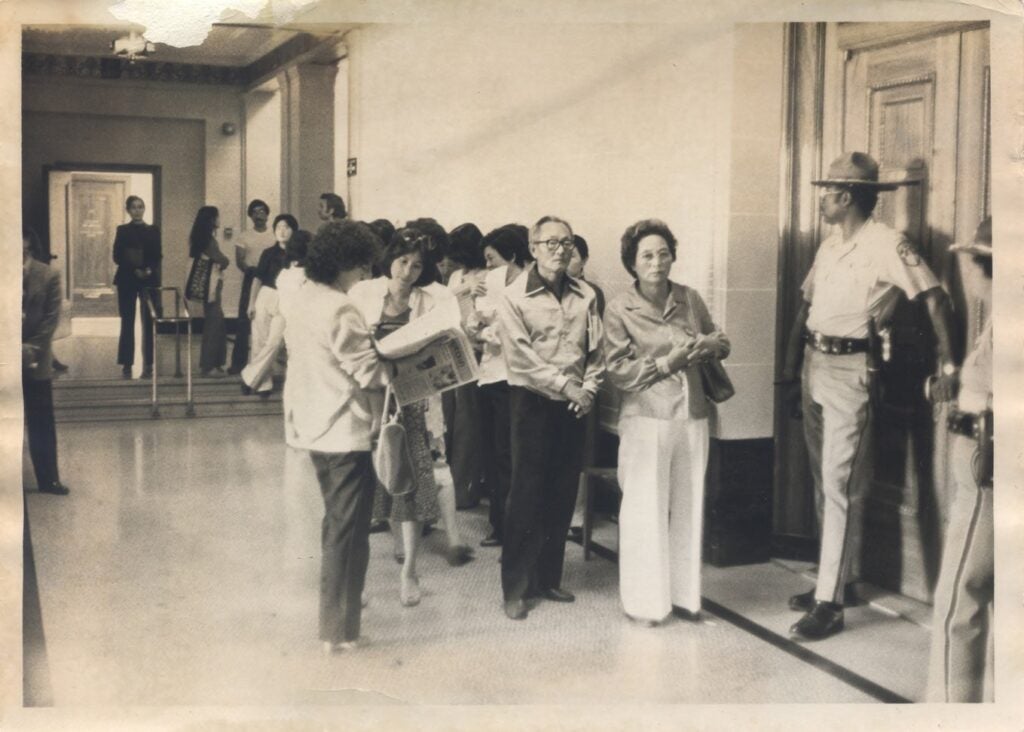

Chol Soo remained on death row while his defense team appealed the 1979 prison-yard conviction and as he awaited a new trial in the Chinatown murder case. When the new trial began in 1982, Chol Soo was not alone like he was for the first one. This time, he had a robust legal team and an entire community behind him. Among those on his legal team was his friend Ranko Yamada, who had become a lawyer by this time and who also served as a tireless leader in the movement to free him.

Image 44.04.06 — Supporters of Chol Soo Lee wait to enter the courtroom in San Francisco, 1982.

Courtesy of K.W. Lee. Metadata ↗

Supporters again packed the courtroom every day. Activist Grant Din remembered how powerful the scene was to witness. “When the trial happened, all the Korean grandmothers would go in the first two rows of the left side of the courtroom,” he described. “We felt that we had the people on his side, on Chol Soo’s side.” 10 Yamada said that “the audience gave the courtroom a conscience.” 11

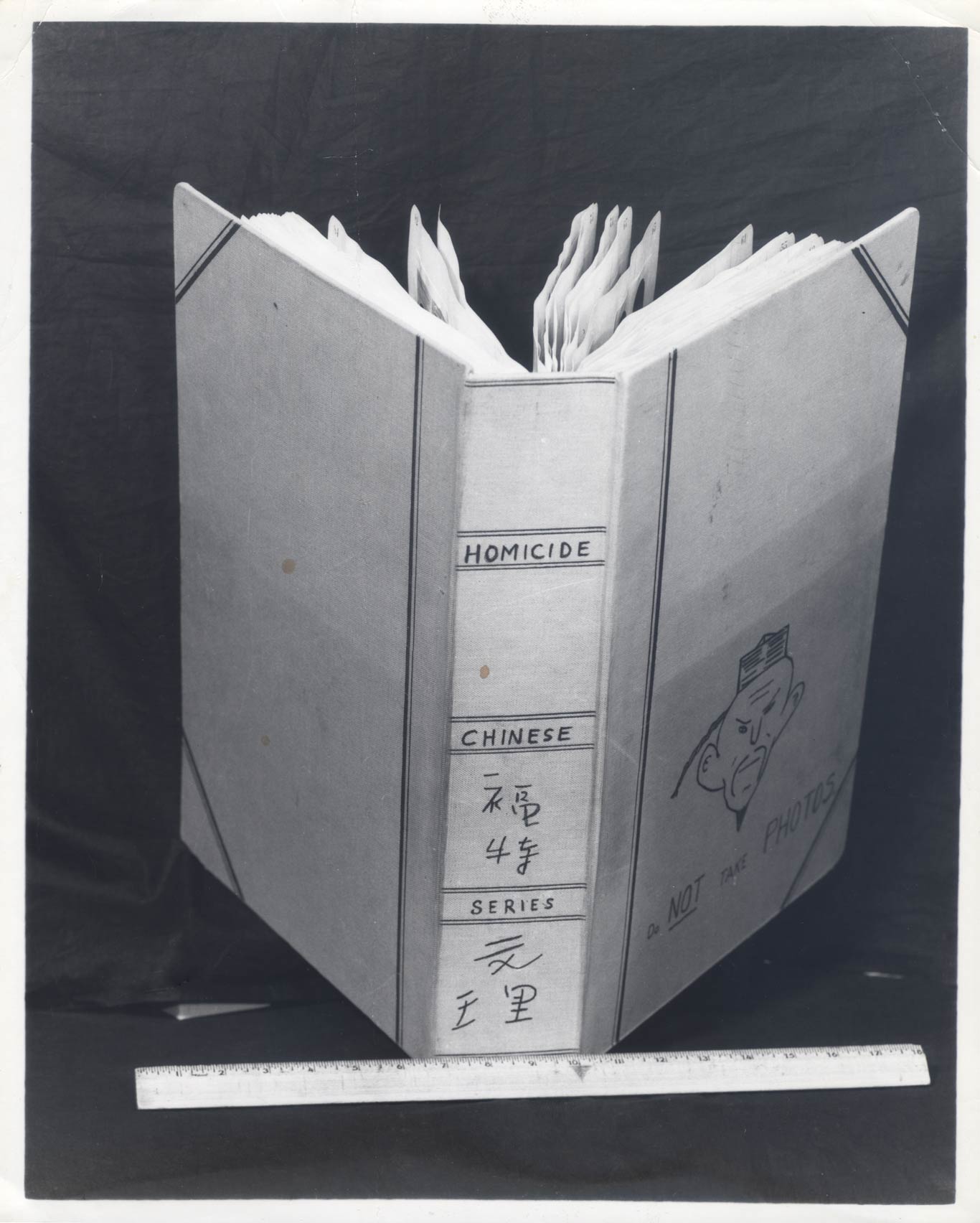

For two weeks, the defense attorneys would pick apart the testimony of the prosecution’s witnesses. A Chinese American witness took the stand for the first time in the murder case and testified that the killer who ran past him after the shooting was not Chol Soo. The defense also showed the jury a picture of the San Francisco Police Department’s Chinatown gang mugbook, which had a caricature with slanted eyes on its cover. Stuart Hanlon, one of Chol Soo’s attorneys, asserted that this offensive drawing showed that “this case started in this kind of racism.” 12

Image 44.04.07 — A photograph of the San Francisco Police Department’s mug book, titled “Homicide Chinese Series,” shows a Fu Manchu-caricaturish drawing on its cover. Chol Soo Lee’s mugshot as a juvenile was in its pages.

Courtesy of San Francisco Police Department. Metadata ↗

On September 3, 1982, a San Francisco jury acquitted Chol Soo of the Chinatown murder. The courtroom erupted in a combination of cheers and tears from his supporters. “It’s like you have just achieved the impossible,” said Yamada, recalling the joyous moment. 13

“My victory is yours,” Chol Soo told his supporters. 14

Despite his acquittal, Chol Soo remained in prison because of his conviction in the prison-yard murder case. But the following year, California’s 3rd District Court of Appeals reversed that conviction. Then, on March 28, 1983, Chol Soo took his first steps into freedom, with TV news cameras capturing the joyful moment. “I’m very grateful for the support and trust that people have given me to free me on this day today,” he told a reporter. 15 He then posed for flashing cameras and hugged his supporters.

Image 44.04.08 — Chol Soo Lee beams at his supporters in Stockton, California, upon being released from prison on March 28, 1983.

Courtesy of Grant Din. Metadata ↗

Chol Soo was incarcerated for a total of ten years. The movement to free him lasted six years and led to the overturning of two murder convictions—a legal victory that many lawyers will tell you is almost impossible to achieve.

“The freeing of Chol Soo was a collective effort,” said activist Warren Furutani. “It took the building, and more importantly the maintaining of a broad united political front; it took the correct presentation of the issue so as to gather the broadest amount of mass support; and it took the conviction, courage, and perseverance of people across the nation to outlast and to bring the legal system to its knees. For this, we always had Chol Soo as a positive example. The movement to free Chol Soo Lee is a community victory and serves as proof that people working as one can create a more equitable society.” 16

Glossary terms in this module

caricature Where it’s used

A picture or description of a person that exaggerates certain characteristics to create a negative effect.

grassroots Where it’s used

A term used to describe a movement or organization that starts with everyday people, instead of people in positions of power.

Endnotes

1Jay Kun Yoo, interview for Free Chol Soo Lee, May 25, 2017.

2 Yoo, interview for Free Chol Soo Lee, May 25, 2017.

3 Ranko Yamada, unpublished interview for Free Chol Soo Lee, July 16, 2017.

4 Karen L. Ishizuka, Serve the People: Making Asian America in the Long Sixties (Verso, 2016), 2.

5Jeff Adachi, unpublished interview for Free Chol Soo Lee, March 16, 2016.

6 Lee, Freedom Without Justice, 4.

7 Yoo, interview for Free Chol Soo Lee, 2017.

8 Jim Wood, “Acquitted Con Credits Asian Community,” San Francisco Examiner, September 5, 1982.

9 Warren Furutani, “Chol Soo Lee: Freedom Without Justice?” Amerasia Journal 10, no. 2 (1983): 81.

10 Grant Din, interview for Free Chol Soo Lee (2022), July 17, 2017.

11 Wood, “Acquitted Con Credits Asian Community.”

12 Stuart Hanlon, “Untitled Chol Soo Lee Legal Case Presentation,” recorded by Christopher Chow at San Francisco State University, 1982.

13 Yamada, interview for Free Chol Soo Lee, 2017.

14 Raul Ramirez, “My Victory Is Yours,” Koreatown Weekly, October 11, 1982.

15 Perceptions: A Question of Justice, produced by Sandra Gin and Tom Nakashima, KCRA, 1983.

16 Furutani, “Chol Soo Lee: Freedom Without Justice?” 88.