TEXT

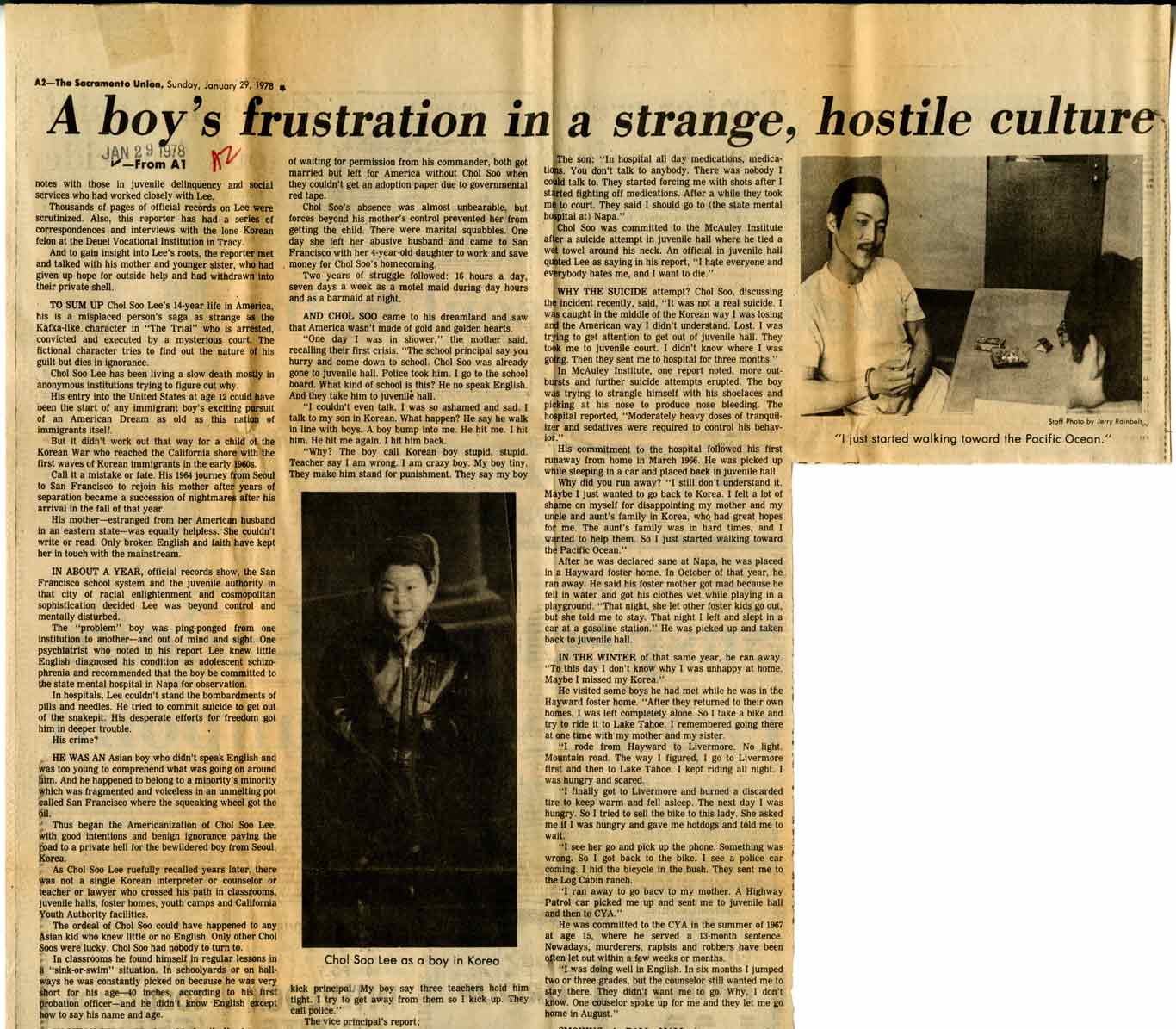

A boys frustration in strange

Object ID

44.03.08

Multimedia details

Creator

Sacramento Union

Publisher

The Sacramento Union

Date

January 29, 1978

Location

Sacramento, California

Language

eng

Type

Text

Format

Article

File Format

jpg

Subject

Newspapers; Self-portraits; Culture; Immigration;

Source

UC Davis Shields Library/Sacramento Union Archive

Credit Line

Courtesy of Sacramento Union Archive, UC Davis Shields Library.

Licensor

UC Davis

MUMI Number

44.03.TXT.026

Creator

Sacramento Union

Publisher

The Sacramento Union

Date

January 29, 1978

Location

Sacramento, California

Language

eng

Type

Text

Format

Article

File Format

jpg

Subject

Newspapers; Self-portraits; Culture; Immigration;

Source

UC Davis Shields Library/Sacramento Union Archive

Credit Line

Courtesy of Sacramento Union Archive, UC Davis Shields Library.

Licensor

UC Davis

MUMI Number

44.03.TXT.026

In Copyright

This Item is protected by copyright and/or related rights. You are free to use this Item in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s).

NOTICES

- Unless expressly stated otherwise, the organization that has made this Item available makes no warranties about the Item and cannot guarantee the accuracy of this Rights Statement. You are responsible for your own use.

- You may find additional information about the copyright status of the Item on the website of the organization that has made the Item available.

- You may need to obtain other permissions for your intended use. For example, other rights such as publicity, privacy or moral rights may limit how you may use the material.

URI for this statement: http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/