Module 5: Silent Pleas

How does the life of Chol Soo Lee teach us about the roles each of us can play in creating a more just society?

In the period just after his release, Chol Soo Lee felt like a celebrity as he went on a tour to thank his many supporters. People even approached him to ask for his autograph. After ten years in prison, he was finally a free man, thanks to a landmark pan-Asian American social movement that formed in his name.

But reentry proved an incredibly difficult process, especially in 1983. Like many formerly incarcerated people, Chol Soo struggled to deal with the trauma of his experiences in prison and to find sustained support after incarceration. He not only carried these mental demons from his incarceration, but also held the weight of a community—and what he felt he owed them—on his shoulders. In addition, he lacked a stable family support system to fall back on. Rather, he had scars dating back to his childhood, from abandonment and abuse by his biological mother, the forced severing of ties with his loving family in Korea, and then his institutionalization in the US.

How did the trauma of being incarcerated for ten years affect Chol Soo Lee after he was freed?

What types of support could have changed the trajectory of Chol Soo Lee’s post-release life? What does his experience reveal about the challenges of reentry for people who are formerly incarcerated?

Why is Chol Soo Lee’s story important today?

Celebrity Tour

The movement to free Chol Soo Lee had grown into a national campaign by the early 1980s, and Chol Soo wanted to express his gratitude to his supporters. “He was truly, truly moved by this groundswell support that came forward for a stranger,” said Ranko Yamada, one of the leading activists in the Free Chol Soo Lee movement and also his friend. “And so he wanted to meet everyone.” 1

On the outside, he seemed to be the model symbol of a successful social movement. He worked part-time at a Korean American social service agency in Northern California. Later, his supporters helped get him various jobs, as a janitor, computer salesman, and labor organizer. But he could not hold on to these jobs.

Chol Soo was often asked to give remarks at various Asian American community events, but he had no background in giving speeches. An audience at the University of California, Berkeley, laughed when he advised students to “do good and study hard,” which was perceived as a surprisingly generic statement coming from someone who had faced a grave injustice and inspired a movement. 2

“You know, [with] the movement … everything happened as we wanted, everything happened as it should,” said Michael Suzuki, who joined the Free Chol Soo Lee movement as a college student and was inspired to become a public defender in Los Angeles. “Up to the time he got released, that was a fairytale, and we thought that, ‘OK, he’s gonna have a fairytale life.’ And that [wasn’t] realistic.” 3

Chol Soo’s ten years in prison made it difficult for him to transition to a so-called normal life outside of it. “You know, there [was] no real training [to learn] how to walk, live an independent life … after you’ve spent so much time in prison,” said Yamada. 4

Activist Warren Furutani observed that Chol Soo had entered prison as a twenty-year-old and left as a thirty-year-old. “Whether the folks who grew to love him wanted him to go to school or get a good job, we were still dealing with a not-so-young adult who only had the education and skills he had when he went to prison,” Furutani said. “There are no long-term paying jobs as a political icon or movement hero.” 5

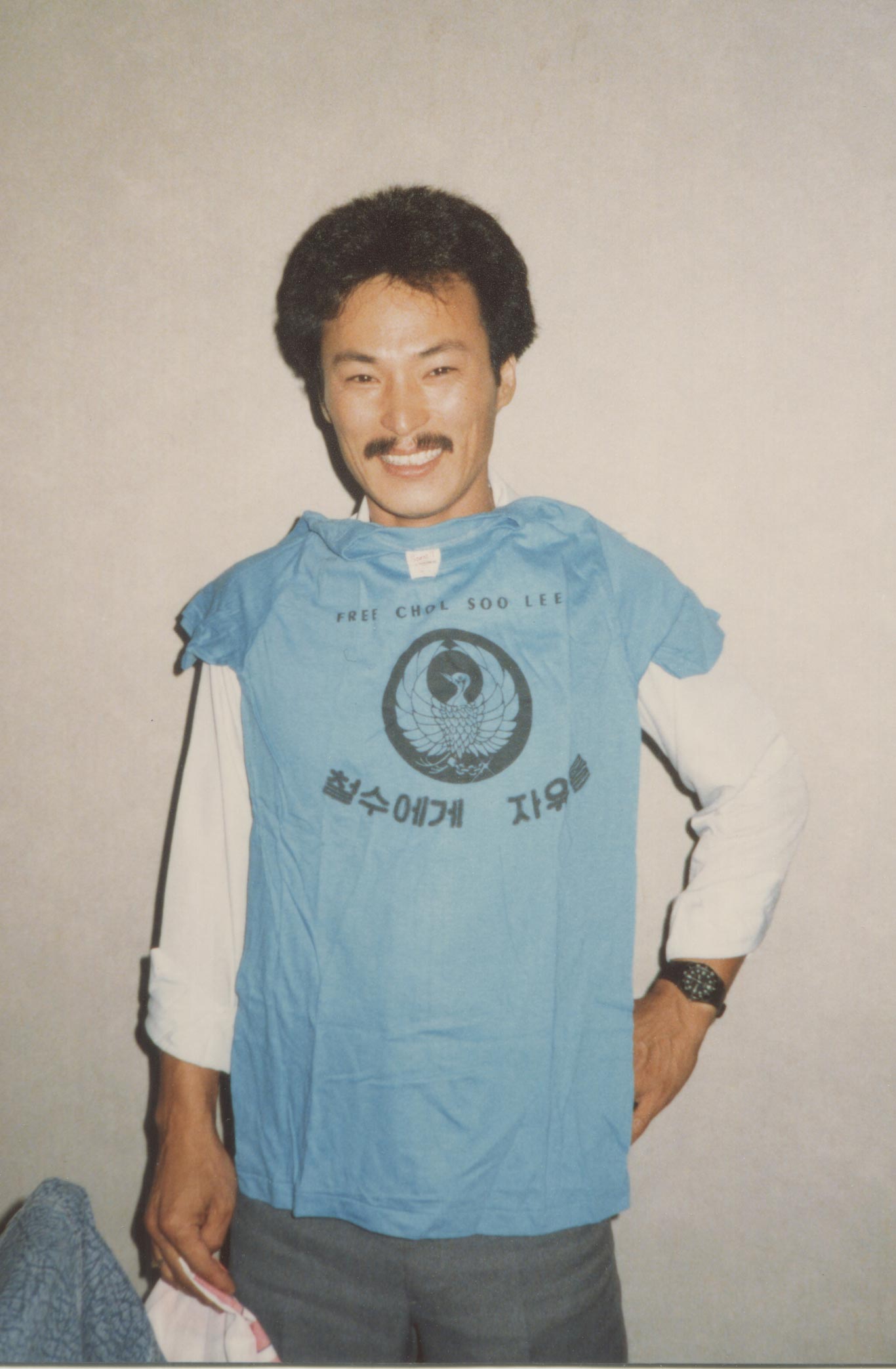

Image 44.05.02 — Chol Soo Lee, pictured here facing the news media and a crowd of supporters in Stockton, California, confronted many difficulties adjusting to a “normal” life on the outside, after his release from prison in 1983.

Courtesy of Grant Din. Metadata ↗

In 1983, at the time of Chol Soo’s release, there were not many rehabilitation programs or much institutional support for formerly incarcerated individuals, according to many of the activists. Such resources could assist with job training, housing, financial knowledge, mentorship, and continuing education. Activist Jeff Adachi, who had joined the Free Chol Soo Lee movement as a college student and became San Francisco’s public defender, noted that even the term “reentry” was not commonly used in the 1980s.

In addition to these challenges, Chol Soo felt indebted to an entire community for winning his freedom. How could he possibly ever repay them? “He felt there was this huge expectation from the community about how he should be after he got out,” said Jai Lee Wong, an activist who started the Chol Soo Lee Defense Committee in Los Angeles. “And he wanted to be that. But then he also had all these demons.” 6

Burning Bridges

Overwhelmed with burden, Chol Soo Lee reached for an escape and self-medicated with drugs. This escalated into a severe cocaine addiction. Close friends tried to get him into a drug rehabilitation program, but Chol Soo’s behavior grew increasingly dangerous. He pulled a knife on his former defense attorney Stuart Hanlon in a desperate attempt to get drug money. Chol Soo became alienated as he descended further into addiction.

Less than ten years after his victorious release from prison, Chol Soo was in and out of jail for drug offenses. Furutani remarked that Chol Soo had returned to a lifestyle of “street survival,” leaving his supporters frustrated. “Many who took him in couldn’t provide the support Chol needed and doors began to close and bridges were burnt, from both sides.” 7

Activist Peggy Saika, who had become close friends with Chol Soo, admitted that his supporters were not prepared for the long term assistance that Chol Soo needed. “When you’ve been incarcerated that long and when you grew up the way he grew up, you need a lot of love and support, and I don’t think the movement was ready to the extent that he needed it.” 8

By 1991 Chol Soo started working for a Chinatown gang for the first time in his life. Ironically, the tough reputation he had gained while in prison made him an attractive recruit for the gang. He was hired to set fire to the gang’s safe house to destroy evidence, but the arson went terribly awry. Chol Soo ended up catching on fire and suffered second- and third-degree burns to more than 75 percent of his body.

Miraculously, he survived. His face—which had formerly graced posters, buttons and T-shirts—was disfigured, and he would be permanently disabled.

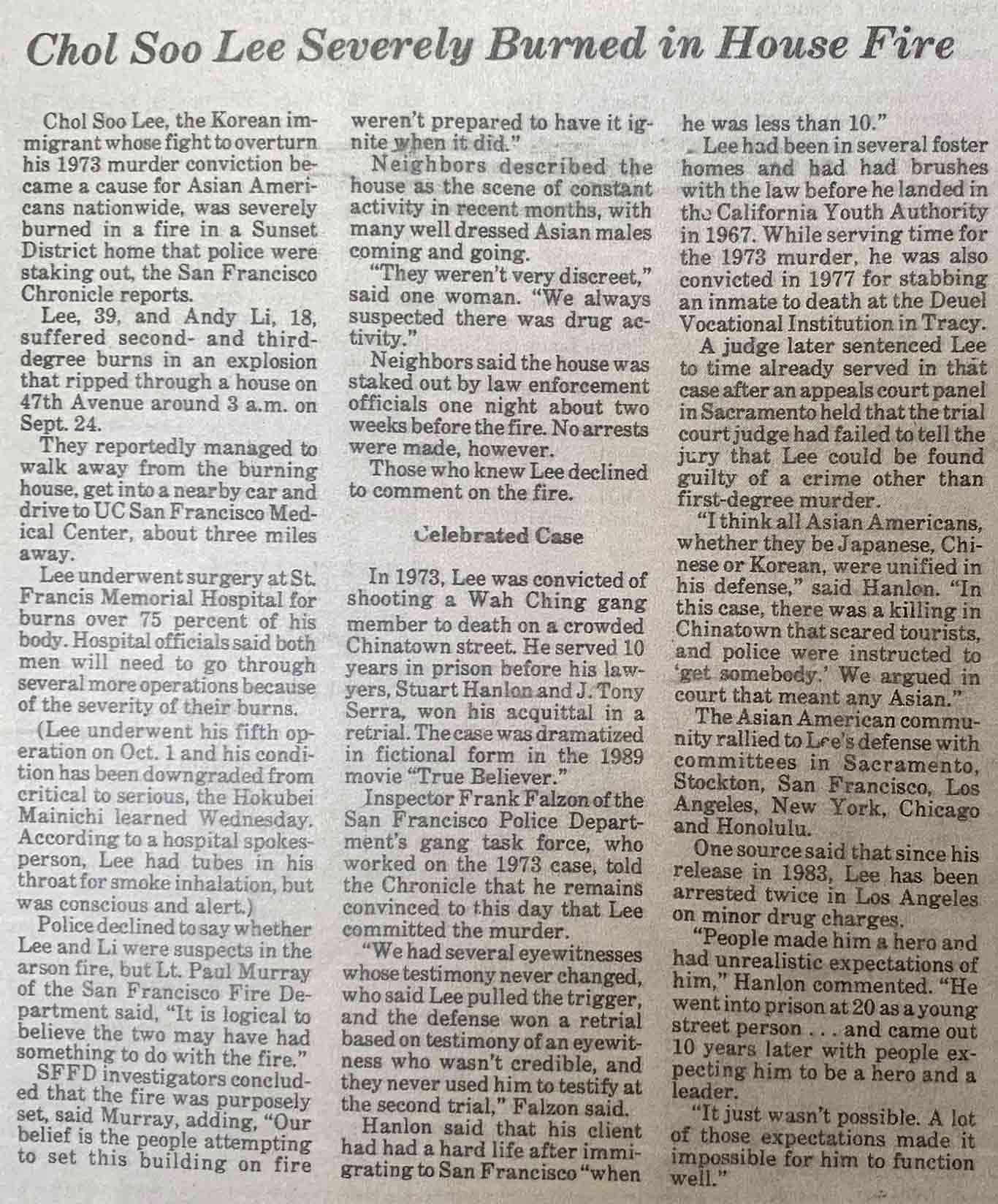

Text 44.05.03 — A news article in the Japanese American newspaper, the Hokubei Mainichi, reports on the arson that severely injured Chol Soo Lee.

Courtesy of K.W. Lee. Metadata ↗

After agreeing to testify against the gang that hired him for the arson, Chol Soo went into the federal witness protection program, assuming new identities and living in remote areas of the country. He would often violate witness protection rules and call journalist K. W. Lee, who had become a father-like confidante, as well as some of the activists closest to him, to escape his loneliness. “He had more problems after his release, demonstrating how far we have to travel for those who come out of prison,” said K. W. “Isn’t that a great irony? In freedom, [Chol Soo] was a deeply troubled man.” 9

Prison Within a Prison

By 2004 Chol Soo Lee decided to come home to San Francisco. He no longer wanted to hide. He was ready to face the community that helped him and to hold himself accountable for his own mistakes.

Finally, he could explain to his supporters why it was so difficult for him to live a “normal life” after ten years in prison. He had been suffering from the psychological demons of his incarceration. “Prison is evil. It destroys every human dignity and humanity has in a person,” he said at a 2006 symposium at the University of California, Davis. “It destroys your spirit, it destroys your mind. And it has destroyed mine, and I’m trying to rebuild it.” 10

Those who are released from prison may be “free” physically, but not always mentally. Adachi concluded that Chol Soo was likely suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) from his experience. He not only faced prison violence, but spent many years in some type of solitary confinement. Incarcerated people refer to solitary as “the hole,” whereby the person is isolated in a single cell with little or no human contact.

“Hole is prison within a prison,” Chol Soo said. “Each time when you’re placed into that solitary confinement, you are there for 10 days, without no books, no nothing. They sent me there quite a few times.” 11

Imagine twenty-two to twenty-four hours per day spent alone in a small cell. This extreme isolation has detrimental effects on mental health long after a person’s time in solitary confinement. Today, several states have passed laws banning or severely limiting the use of solitary confinement in prisons because of the long-term harm it causes people.

Between 1979 and 1982, Chol Soo was placed in another type of isolation; he was isolated as a condemned man on death row after being convicted of murder in the prison-yard killing that Chol Soo said was in self-defense. He would later write in his memoir that everyone on death row thought about suicide. He wondered if the prison system drove death row inmates to depression on purpose, so they would take their own lives.

A Silent Plea

Knowing the dark times Chol Soo Lee was enduring while in prison, journalist K. W. Lee encouraged Chol Soo to write and tell his story. From death row, Chol Soo wrote a poem titled “A Silent Plea,” inspired by another condemned man who had tried to take his own life before his execution.

Who knows the man in pale cell?

Who knows what man is thinking in his last thoughts?

Who hears this man’s plea and prayer for life?

Only the silence from God and people prevail.

Chol Soo felt a deep connection to the person’s pain. “He was pleading for his life, for his last chance at life, and there was no one who was hearing it,” said Chol Soo, explaining the poem. “And the plea, his plea was the same as my plea, looking for some sense of light and justice. Whether he was innocent or not, I have no idea, but his pleas were totally ignored, and it was just silence.” 12

Chol Soo contrasted the world outside of prison with the silent torture within the prison walls: “As the pale cell darkens in blood / The world asleeps (sic) peacefully / Dreaming to not to hear man’s silent plea and prayer.” He felt like society willfully ignored the suffering of its incarcerated population.

Second Chances

Mass incarceration is among the most pressing issues of our time. The United States leads the world in incarceration, holding 5 percent of the world’s population, but almost 25 percent of its incarcerated population. Instead of being a place for rehabilitation and reform, data shows this is not the case. Data from the federal Bureau of Justice Statistics found that 66 percent of released state prisoners were rearrested within three years, an issue referred to as recidivism.

Communities most affected by incarceration and their allies have advocated for change. There are now programs and more educational opportunities in prisons to better prepare incarcerated people for life on the outside. The Bard Prison Initiative, a rigorous college program offered in New York state prisons, has an almost nonexistent recidivism rate among its graduates. While these outcomes are promising, there are not enough of these programs.

Some activists and organizations involved in the prison abolition movement are pushing for more radical change, including the dismantling of prisons in favor of the building up of support systems, like health care, housing, education, and employment, which would help address the root problems of crime.

Today, at San Quentin State Prison, where Chol Soo Lee was on death row, rehabilitation programs include a long-distance running club, yoga, and an award-winning newspaper run by the incarcerated. In 2023 California Governor Gavin Newsom announced the prison would be transformed into a rehabilitation facility in an effort to treat people more humanely and to prepare them to return to society.

More to explore

Text

San Quentin News

The San Quentin News, an incarcerated-produced newspaper based at San Quentin State Prison, prints 35,000 newspapers each month. It is supported by foundations and donations, and distributed to more than 30 state prisons and four juvenile facilities.

But even if such reforms existed when Chol Soo was at San Quentin, he may not have benefited. Typically, those on death row are excluded from such programs.

Once released from death row and prison, Chol Soo never forgot about the people locked up with him. He also did not distinguish between those who were guilty of their crimes and those who were not when speaking out publicly about the human damage of incarceration. Instead, he talked about the need for a foundation to support incarcerated and formerly incarcerated Asian Americans in order to address the specific needs and conditions of this population.

The Asian Prisoner Support Committee, the New Breath Foundation, and API-RISE are some of the organizations that exist today. Given the strong stigma many incarcerated and formerly incarcerated Asian American and Pacific Islanders face within their own community, these organizations provide a lifeline and community for many.

Image 44.05.06 — Chol Soo Lee, at a 2007 symposium at the UCLA School of Law. He told the audience, which included activists and the legal defense team who helped free him, “I’m not a hero. I’m just a human being.”

Courtesy of Sangjin Kim, The Korea Daily. Metadata ↗

“A Silent Plea” concludes with the following lines, addressed to Chol Soo’s death row companion:

Let my living soul be your warmth to pass your nights in company

But soon, I too may join your wondering cries for justice in spirit.

But so long as I am living

My soul will hear your silent plea for justice …

Despite often being stuck in a cycle of punishment and isolation, Chol Soo maintained a determination to connect with others. In this poem, he offered his death row companion his own warmth to alleviate the other’s loneliness. Even though he knew he himself might also be put to death, he vowed to keep the person’s cry for justice alive. Perhaps Chol Soo’s remarkable ability to maintain his own sense of humanity, despite the dehumanizing treatment he received while incarcerated, can inspire all of us to listen for the silent pleas that call out to us today. In doing so, each of us can play a role in fighting for a more just society for all and carrying on a meaningful legacy for Chol Soo Lee.

Glossary terms in this module

federal witness protection Where it’s used

A program of the U.S. Department of Justice designed to protect witnesses, along with their family members, before, during, and after legal proceedings whereupon those witnesses have an association with the federal government and provide testimony. Witnesses and their families typically get new identities and relocation support to ensure their safety.

mass incarceration Where it’s used

This term refers to the massive increase in the number of incarcerated persons in prisons and jails in the US starting in the mid-1970s and that continues today. The US incarcerates more people than any nation in the world.

post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) Where it’s used

A mental health condition caused by an extremely stressful or terrifying event. Symptoms may include flashbacks, nightmares, severe anxiety and uncontrollable thoughts about the event.

recidivism Where it’s used

This term refers to the tendency of formerly incarcerated persons to recommit crime and/or return to the criminal justice system. Because prison is a traumatizing experience and there is a lack of rehabilitation programs and reentry support, formerly incarcerated people often find returning to life outside of prison extremely difficult, sometimes returning to committing crime.

reentry Where it’s used

The process of transitioning back into the community after imprisonment. After imprisonment, formerly incarcerated people often struggle to adjust to life outside of prison.

Endnotes

1 Yamada, interview for Free Chol Soo Lee, 2016.

2 Chol Soo Lee, “Public Remarks at San Francisco State University,” February 13, 2008.

3 Michael Suzuki, interview for Free Chol Soo Lee, May 27, 2017.

4 Yamada, interview for Free Chol Soo Lee, 2016.

5 Furutani, “We Freed Chol Soo Lee, Now What?,” 48.

6 Jai Lee Wong, interview for Free Chol Soo Lee, May 22, 2017.

7 Furutani, “We Freed Chol Soo Lee, Now What?” 49.

8Julie Ha, “Free, Free Chol Soo Lee,” KoreAm Journal, December 29, 2014.

9 Ha, “Free, Free Chol Soo Lee.”

10 Chol Soo Lee, “UC Davis Chol Soo Lee Symposium Remarks,” Courtesy of Richard S. Kim, University of California, Davis, February 22, 2006.

11 Richard S. Kim, “A Conversation with Chol Soo Lee and K. W. Lee,“ Amerasia Journal 31, no. 3 (2005).

12 Kim, “A Conversation with Chol Soo Lee and K. W. Lee.“