Module 1: An Introduction to Vietnamese Americans

Has leaving Vietnam as refugees impacted what it means to be Vietnamese American?

The Vietnamese American experience challenges us to rethink what we might know about history, identity, and power in the United States. This chapter examines the effects of French colonialism and US militarism on Vietnamese identity and culture. This chapter also centers Vietnamese perspectives and stories as it explores refugee resettlement and community building in the post-Vietnam War years.

This first module is a brief overview of the history of Vietnam, which provides essential context for understanding the challenges faced by Vietnamese Americans and their diversity of experiences. We will consider the history of Chinese occupation, the period of French colonial rule, and the era of American militarism in Vietnam as broader frames for situating the struggles and resilience of the Vietnamese diaspora.

How are refugees different from immigrants?

Why did Vietnamese Americans come to the United States?

What are the effects of colonialism and militarism on the Vietnamese people and their homeland?

Origin Stories of Vietnam

Vietnamese Americans and their descendants come from an S-shaped country that has been called “Việt Nam” since the 1800s, but has been known by many other names in ancient times and before the intervention of Western colonizers as well. Văn Lang, Âu Lạc, Đại Việt—these historical names represent the shifting identity of a nation with borders that were in perpetual flux. Like other places in the world, the nation-building in this part of Southeast Asia involved displacements of Indigenous peoples, clashes with nearby states for territory and power, and the creation of cultural narratives that have come to shape our knowledge about its past.

Image 19.01.01 — Map of Vietnam and bordering nations in Southeast Asia.

Courtesy of UCLA Asian American Studies Center. Metadata ↗

The origin story widely told about Vietnam is that the people were born from the union of Lạc Long Quân, a dragon king from the sea, and Âu Cơ, a fairy princess from the mountains. Together Âu Cơ and Lạc Long Quân had one hundred children who became the ancestors of the Vietnamese people. Their irreconcilable affinities to the sea and the mountains drove them apart. However, according to the legend, they divided their children so that fifty would go with their father to the sea, while the other fifty followed their mother to reside in the mountains of what would become northern Vietnam. Hùng Vương, ruler of the Văn Lang nation in 2879 BCE, is said to be the couple’s firstborn son.

Origin stories were passed down from one generation to the next to offer communities a sense of cultural cohesion and an imagined connection to each other. Such was the case with the legend of Lạc Long Quân and Âu Cơ, which is not only about how the Vietnamese people came to be, but how the land’s geography shaped their identity.

Vietnam’s eastern boundary is the South China Sea, with China to the north, and Laos and Cambodia to the west. The land’s location at the edge of a vast body of water has influenced the way that Vietnamese people narrate their stories. In addition to the numerous water-based metaphors and themes in Vietnamese writing and folklore, the Vietnamese word nước is a term that means both water and country, or homeland. Vietnamese American scholar Huỳnh Sanh Thông explains that “the most significant meaning of nước as ‘water’ is the concept of people who have gathered near a body of water to grow rice for one another, and founding a stable community, sharing rain and drought, plenty and famine, peace and war.”1

Histories of Colonialism and Resistance

Vietnam’s long history is marked by eras of peace and war. Colonialism was, more often than not, met with resistance by the Vietnamese people. For thousands of years, China attempted to rule Vietnam and was met by fierce opposition, as seen through the examples of Vietnamese revolutionary leaders such as Hai Bà Trưng (c. 14–43 CE) and Lê Lợi (1384–1433), who mobilized for sovereignty. Clashes with China continue to the present day over claims to land and water, as well as over history and identity.

Image 19.01.03 — This panel depicts Hai Bà Trưng (the common name of two sisters, Trưng Trắc (徵側) and Trưng Nhị (徵貳)) leading an army of foot soldiers. The attention to detail in this lacquered panel reflects the significance of these revolutionary leaders.

Courtesy of Sacramento State University Library, Donald and Beverly Gerth Special Collections and University Archives. Metadata ↗

Accounts of European colonialism in Asia traces back to the fifteenth century, but in Vietnam, the most profound Western influence can be traced to the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, when the Portuguese entered Southeast Asia to gain trade monopolies and to spread their religion. They influenced Vietnamese culture through the lasting transformation of the language. Unlike the writing systems of their northern and western neighbors, Vietnamese is now written in a romanized script.

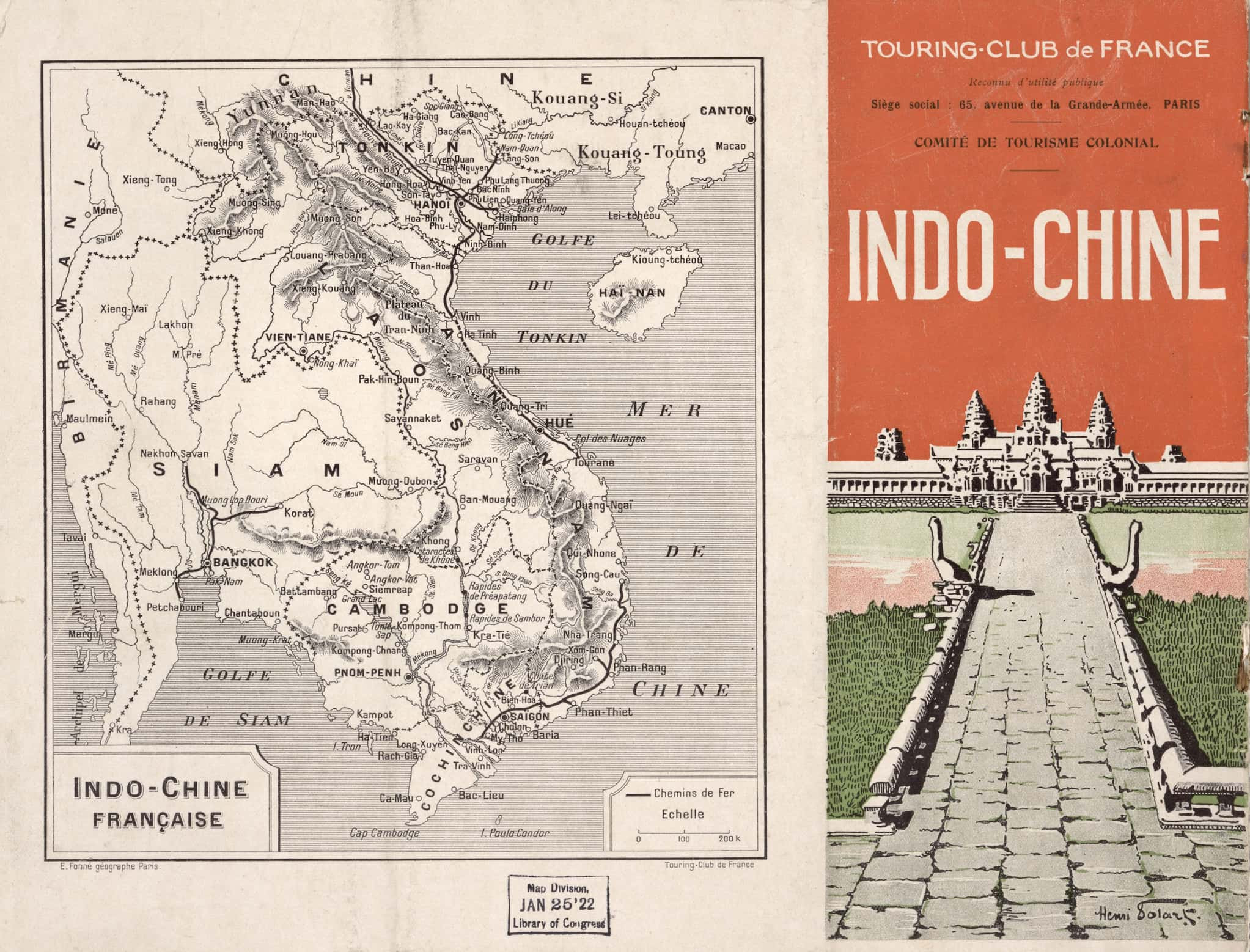

In the early nineteenth century, France colonized the Southeast Asia region, staking a claim to Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam. The French renamed the area encompassing these three countries “Indochina” and referred to all Cambodian, Laotian, and Vietnamese people as “Indochinese.” It should be noted that Indochina and Indochinese were political terms imposed on a land and its people and are not widely adopted or used by the Vietnamese people or other Southeast Asian communities to refer to their country or identities.

Image 19.01.04 — This French publication (c. 1910) depicts a map of Indochina, formerly known as French Indochina or Indochine Française until 1950. The term “Indochina” refers to the blending of Indian and Chinese cultural influences in the region.

Courtesy of World Digital Library. Metadata ↗

Colonialism changed Vietnam and its people in both drastic and subtle ways. France exploited the country for its strategic location for trade and expansion of power in Asia, which included spreading Christianity. France also extracted natural resources such as rice and rubber, and the labor of the Vietnamese people.

In 1906, Phan Châu Trinh, a revolutionary leader, wrote a letter to French colonial administrators to represent the will of the people:

“In Vietnam today the opinion of the common people, whether they be intelligent or stupid, is that the Protecting Power mistreats the Vietnamese; that it does not consider them as human beings…For the Vietnamese people, that represents the designs of colonialism.” 2

What Phan explained was the dehumanization of colonial subjects that occurs in tandem with the occupation and exploitation of their land.

During the hundred years of colonial rule, Vietnamese culture also adapted to incorporate more French influences, as can be seen in the architecture, education systems, and food. Products of French colonialism include coffee (cà phê) and bread (bánh mì), two staples of Vietnamese cuisine still popular today.

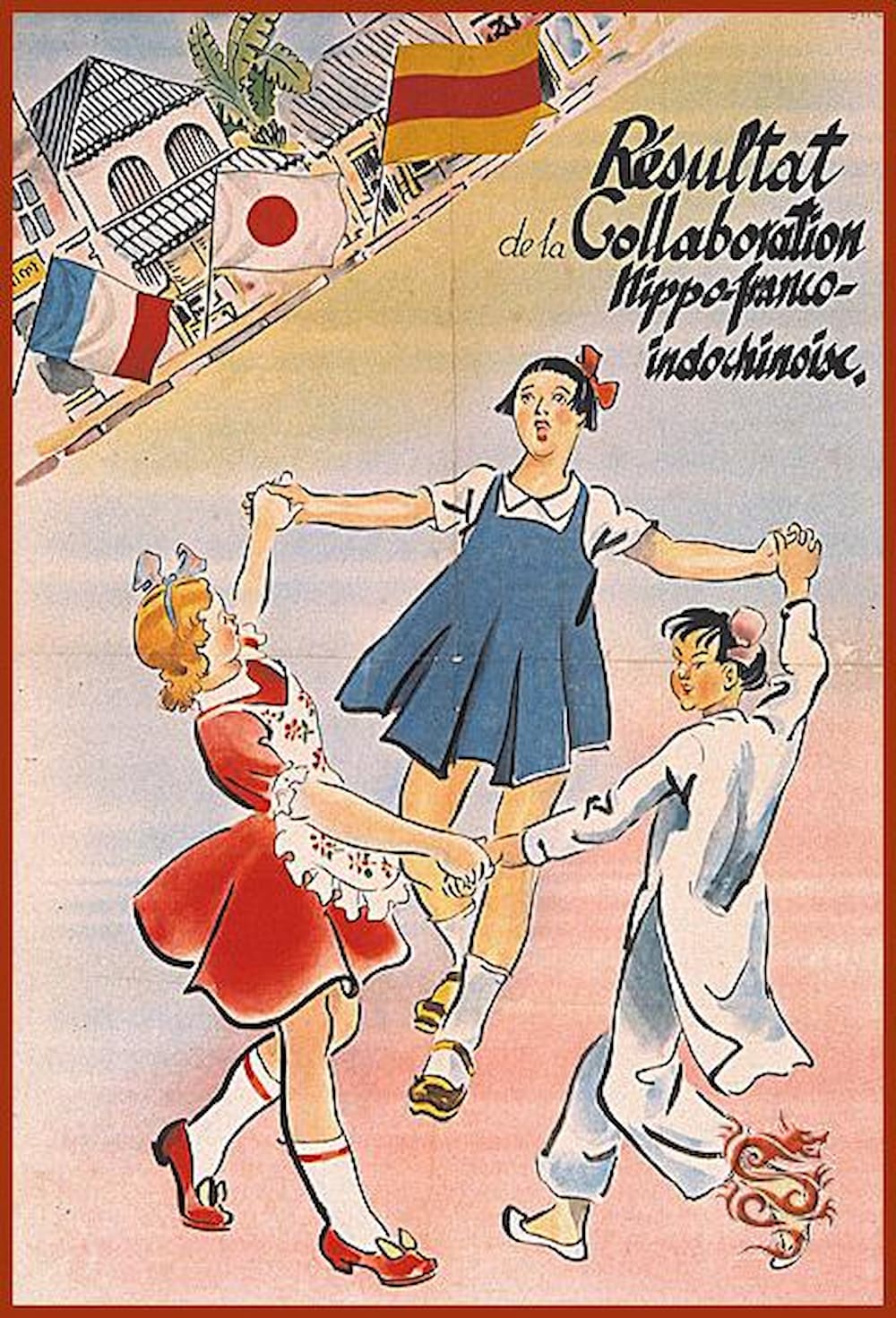

During World War II, Vietnam’s coastal location made it a desired military post for warring superpowers. While Vichy France remained in control of the country, Japan also occupied military bases in Vietnam during the war. In March 1945, however, Japan took direct control of Vietnam from France until the end of the war in August 1945.

Image 19.01.05 — A Japanese propaganda poster celebrating colonialism framed as “collaboration” between France, Japan, and Vietnam.

Courtesy of Wikimedia. Metadata ↗

By the end of WWII, the Việt Minh, a nationalist and Communist group led by revolutionary leader Hồ Chí Minh, had made significant gains in their goal of freedom from foreign rule. The French sought to regain colonial power, in what scholars refer to as the First Indochina War (1946–1954). At the famed battle of Điện Biên Phủ, the Việt Minh defeated the French, leading to the end of French rule in Vietnam.

At the international Geneva Conference of 1954, Vietnam was divided at the seventeenth parallel into two zones. The Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam) was established by the Việt Minh. The State of Vietnam (South Vietnam) also formed a new government, later renamed the Republic of Vietnam, and was supported by the United States. This partition resulted in approximately one million Vietnamese fleeing from north to south, a number of them Catholics fearing a Communist regime that posed a significant threat to their faith.

Multiple Perspectives of the Vietnam-American War

During what is commonly referred to as the Vietnam War in the United States, the Soviet- and China-backed North Vietnam, and US-backed South Vietnam were at war for two decades, from 1954 to 1975. Some scholars have called this period the Second Indochina War. In Vietnam, the war has also been called the American War.

Throughout this chapter, we will refer to this period of US militarism as the Vietnam-American War to call attention to the multiple perspectives and lived experiences of a conflict that devastated the land and its people. This war shows why many believe that US militarism was among the main catalysts for driving Vietnamese people out of their homeland and why the largest Vietnamese diaspora can be found in the United States. While the Vietnam-American War is chronicled as ending on April 30, 1975, the refugee exodus continued for decades after.

When considering the history of the war and collapse of South Vietnam, Vietnamese Americans who identify as refugees or descendants of refugees usually adopt the Fall of Saigon perspective, whereas Vietnamese people who remained and were born in postwar Vietnam often adopt the lens of “Liberation Day.”

There is a whole spectrum of perspectives and feelings that are obscured by these two oppositional memories. Unlike migrants who choose to leave their home for better conditions and are usually able to return, refugees are forced to flee their homelands due to political persecution. Their departures are often hurried, and refugees usually experience uncertainty in seeking asylum and safety. Such was the case for many Vietnamese refugees. The displacement of human beings from their ancestral homes is one of the terrible effects of war.

The Beginnings of Diaspora

A few hundred Vietnamese people lived in the United States before 1975, but due to their relatively small numbers compared with other Asian American groups, there is limited research documenting Vietnamese American communities during this period. Before and during the Vietnam-American War, there were international students from Vietnam studying in US high schools and colleges; many remaining in the country at the war’s end. There were also Vietnamese military officials in training in the United States who remained. A handful of Vietnamese women who married American men, referred to as “military brides” or “war brides,” also lived in the US.

The end of the war and the collapse of South Vietnam in 1975 led to a mass exodus of Vietnamese from their homeland; many different groups of refugees fled by land and sea starting in the late 1970s through the 1990s, with more arriving as immigrants to reunite their fractured families.

The Vietnamese global diaspora today numbers over five million people, with over two million in the United States alone. Scattered outside Vietnam (which has a population of over ninety-eight million), this people’s history of displacement helps us reframe belonging, identity, and community.

Vietnamese Americans’ diverse regional, class, educational, and gendered experiences should be considered while learning about their stories of exodus and migration, and how they rebuilt lives in the aftermath of war and in new lands. Some members of the diaspora may not identify as “Vietnamese American” or “Asian American,” but their displacement outside of a shared ancestral homeland ties them together in an “imagined community,” for better or worse.

Glossary terms in this module

asylum Where it’s used

The protection granted by a nation to someone who has left their established or ancestral homeland as a political refugee.

colonialism Where it’s used

When one country takes partial or complete control over another country economically and politically, which can include exploiting its natural resources for profit. The colonizer imposes their belief system and ways of life onto the colonized.

dehumanization Where it’s used

The process of depriving a person or group of people of human qualities or attributes such as compassion, dignity, and individuality.

diaspora Where it’s used

The dispersal, movement, migration, or scattering of a people from their established or ancestral homeland.

Fall of Saigon Where it’s used

Refers to the collapse of the South Vietnamese capital on April 30, 1975, marking the end of the Vietnam-American War. For Vietnamese people who remained after the war, this date is often referred to as “Liberation Day.”

militarism Where it’s used

The belief in and use of force, including full-scale war, to assert power, authority, and control over a nation or people.

refugee Where it’s used

A person who has been forced to leave their country in order to escape war, persecution, or natural disaster.

Endnotes

1 Huỳnh Sanh Thông, “Live by water, die for water,” in Watermark: Vietnamese American Poetry & Prose, eds. Barbara Tran, Monique T.D. Truong, and Luu Truong Khoi (The Asian American Writers’ Workshop, 1998), 7.

2 Bửu Lâm Trương, Colonialism Experienced: Vietnamese Writings on Colonialism, 1900—1931 (University of Michigan Press, 2000), 84.