Module 7: Southeast Asian Youth Activism From Reform to Abolition

Was Asian American Activism successful in improving the lives of Asian Americans?

Note from the authors:

We are grateful to the organizers at the Providence Youth Student Movement, including Daniel Chhum, Linda Heng, Suonriaksmay Keo, Justice Gaines, and Vanessa Flores-Maldonado, for sharing their experiences and teaching us about the transformative power of youth organizing. We also thank Jon Salunga for his wise and generous comments which challenged us to think more deeply about Ethnic Studies teaching pedagogies and our responsibility as instructors.

How did the Providence Youth Student Movement create community safety in the city? What are the limits of legal reform?

What is abolition? How and why did the Providence Youth Student Movement youth develop abolitionist programs for their communities?

What is the importance of mutual aid?

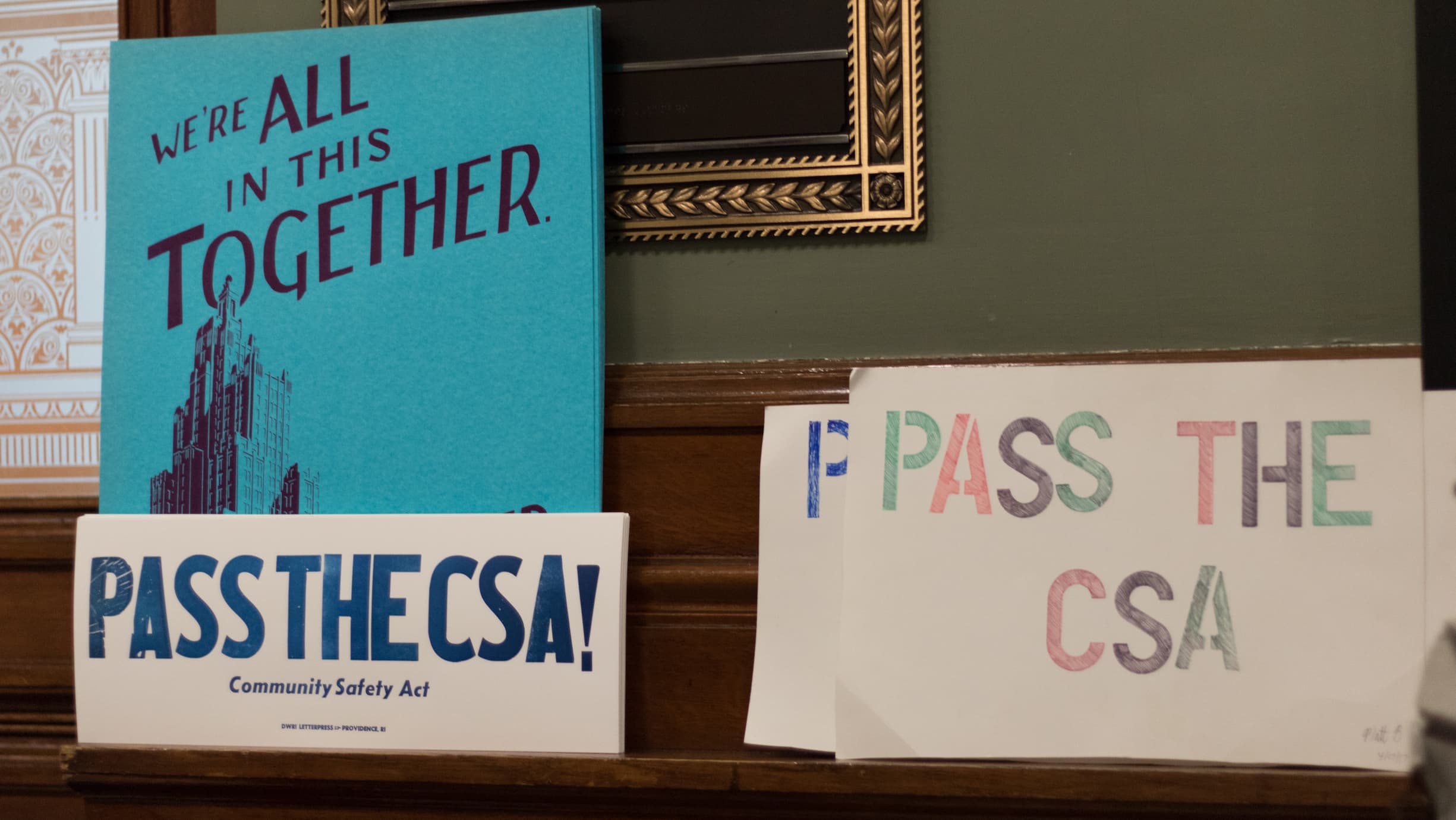

Youth Power: Community Organizing and the Community Safety Act

In 2012, the Providence Youth Student Movement (PrYSM) united with local organizations to form a coalition and mobilize a powerful campaign that would make their vision of community safety in Providence a reality. The coalition engaged in community organizing, a process that mobilizes everyday local people to come together, identify the issues that most affect their community, and create solutions for positive change. Their efforts culminated in the Community Safety Act (CSA), a community-authored law that banned racial profiling, eliminated the police department’s database of alleged gang members, and protected the rights of LGBTQ+, undocumented, and Southeast Asian community members. This module discusses the ways in which organizations can create community safety, and how mutual aid networks benefit these communities as well.

For five years, PrYSM youth were an integral part of the campaign and worked closely with members of the larger coalition to create social change at the community level. They met regularly to discuss their strategies and goals for the citywide campaign. Together, they identified allies who would support the law and opponents who would try to block it. They built local support for the CSA by door-knocking, phone banking, and speaking with residents about the need for police accountability and safer neighborhoods. They also organized public actions, including community marches to City Hall, where PrYSM organizer Justice Gaines reminded elected officials of their duty to serve the people:

“We’ll protect our people. We’re gonna speak up the way we need to speak up, and we’re gonna challenge you the way we need to challenge you. Y’all are public servants, not the other way around… Y’all are here to work for us.” 1

PrYSM organizers also played a powerful role in co-authoring the multi-layered CSA. Drawing on their lived experiences, organizers provided crucial insights about safety that shaped each section of the CSA. Recalling the incident when she witnessed the police illegally profile young men and enter their names into the gang database, Linda Heng insisted that the CSA protect the rights of minors to be notified if they get in trouble with the police.

Suonriaksmay Keo remembered the police harassment that her brother endured and the strain it placed on her family. She strongly advocated for protections against racial profiling and the elimination of the gang database. Specific sections of the CSA were added to protect youth during police interactions to prohibit Providence police from harassing youth, photographing or video recording them, and asking about their immigration status. The CSA also gave youth the right to know if they were registered in the police department’s gang database and, if so, the right to appeal. Linda, Suonriaksmay, and other PrYSM organizers demonstrate that the people most impacted by police misconduct have the best insights into creating a new vision of community safety.

Developing the CSA was not an easy process. It took the coalition three years, dozens of community strategy meetings, and more than thirty drafts to write and finalize the CSA. Each draft of the bill involved meetings with various stakeholders, including PrYSM representatives Justice Gaines and Linda Heng, their attorney, city officials, police leadership, and representatives from the mayor’s office.” 2 Linda, the youngest member of the negotiation team, worked especially hard to make sure that PrYSM’s vision of community safety was accurately represented in the CSA.

Despite these challenges, Linda and Justice were inspired by how these community strategy meetings and the movement brought various community members together to fight for a shared goal. Justice states:

“I think back to those meetings with such love and respect, because we were in a room with dozens of people from multiple organizations and multiple walks of life, looking at this thing folks worked really, really hard on, saying, “We want to win. How do we do it, and how do we do it together?” 3

By deciding to continue standing together and doing the difficult work of organizing across their differences, PrYSM youth and the coalition were able to build the power and solidarity they needed to sustain the campaign. They refused to let their differences divide them and instead found power in building a collective strategy to protect their community.

During the most challenging moments of the lengthy campaign, PrYSM youth used their many talents to inspire and re-energize their community. Longtime PrYSM member Daniel Chhum explains that the distinct forms of ingenuity and creativity that PrYSM youth brought to the movement amplified the campaign’s goals and messages while also helping PrYSM youth discover how to use their imagination for a shared purpose:

“It’s the energy. It’s how radical we are… It’s the creativeness around our signs. It’s how we are able to blend different trends together to make it popping… We’re able to dance out there and be expressive, because we’re still learning about ourselves, too. We’re out here, makin’ a fool out of ourselves, but we love it, though!” 4

PrYSM youth showed Providence that “youth creativity is youth power.” 5 They used their imagination to put their own spin on common activism tactics, like direct action and demonstrated the power of bringing authenticity, creativity, and joy to their work in order to sustain a multi-year campaign and carry out their visions.

The love and care with which PrYSM youth led the CSA movement had lasting impacts on the organizers, who, according to PrYSM executive director Vanessa Flores-Maldonado, “really learned the power that an individual has when they are so connected into their community and listening to their community and working alongside the community.” 6 As PrYSM youth struggled with confronting the power that police held over their sense of safety and dignity, they simultaneously regained their own sense of power by being in community with others across the city. In community, the youth transformed disempowerment and disrespect into a movement for abolition.

The Limits of Legal Reform

The Community Safety Act passed in June 2017, marking a historic policy win for the Providence Youth Student Movement and Southeast Asian communities. In addition to prohibiting Providence police from racially profiling and criminalizing youth, the CSA guaranteed new legal protections for vulnerable communities. For example, trans and non-binary individuals could request to be searched by an officer of their preferred gender, the police department removed the gang database, and Providence was named a sanctuary city for undocumented immigrants at a time when the fear of deportation was high. PrYSM also invested significant energy into building the Providence External Review Authority (PERA), a review board to track, investigate, and respond to complaints of police misconduct.

In the years that followed, however, the implementation of the CSA’s provisions was inconsistently enforced. Providence police continued to violate the provisions and community members’ rights, leading PrYSM to file several lawsuits against the police department. Additionally, important police accountability processes, such as PERA, were ineffective. Although the CSA was impressive on paper, it was poorly implemented in practice.

PrYSM organizers quickly realized that legal reforms like the CSA fell short of the vision for community safety that they sought to realize. Legal reforms are changes to the law such as bills, acts, and legislation that are designed to address existing problems and inequities in society. While legal reforms may appear promising on paper, they often do not eliminate inequality in practice when they are not enforced. As a result, the CSA failed to protect and empower vulnerable communities, forcing PrYSM to reexamine its priorities and its strategy.

“We’ll Protect Our People”: PrYSM’s Community Defense Project

PrYSM organizers realized that relying on external government systems to protect them was not producing the safety their communities needed, so they began to re-envision what it meant to create community safety. Typical rapid responses to emergencies, for example, often involve calling 9-1-1 and inviting law enforcement into the community. As an alternative to relying on the police, youth imagined community-based systems of support run by community members themselves.Rather than contacting the police, residents could call on each other instead. This is an example of mutual aid where community members collaborate and share resources to support each other’s needs. Mutual aid networks are characterized by generosity, solidarity, and care. They are a form of neighborhood activism that challenges ineffective state-run systems and puts power back in the hands of the people.

In this spirit, PrYSM organizers founded the Community Defense Project (CDP), which “empowers Southeast Asian youth and youth of color to know: their rights when interacting with law enforcement, what actions to take when their rights are violated, and how to educate their communities on their rights.” 8 The CDP was inspired by the community-run programs implemented by the Black Panther Party and other abolitionist grassroots organizations in the Black liberation movement.

The CDP provides free and low-cost legal support, community safety classes, and political education about abolition in Providence. Youth organizers offer free “Know Your Rights” workshops, facilitate copwatch trainings, and run a community hotline for residents to report police or domestic violence in their neighborhoods. The CDP also mobilized childcare networks to support working parents and provide peer-led support groups for youth to discuss and heal from their lived experiences of police violence.

At the heart of the CDP is PrYSM’s enduring recognition that the community’s most urgent issues are best determined and addressed by community members themselves, not the police. The CDP formed new community-based systems of care as an alternative to calling the police for support. Believing that “strong communities make police obsolete,” PrYSM youth turned to each other to create the safety that their communities wanted. 9

PrYSM’s community organizing to address the root conditions of community safety aligns with a deeper vision of abolition. Abolition understands that marginalized communities are more often harmed by policing than protected by it. Instead of racially profiling and criminalizing communities, abolition transforms societal problems by tackling their root causes and providing communities with basic needs, such as housing, health care, education, food, and clean water and air. Rather than investing in systems of policing and prisons, an abolitionist vision invests in the fundamental, everyday needs of people, which create the necessary conditions for safer, healthier lives.

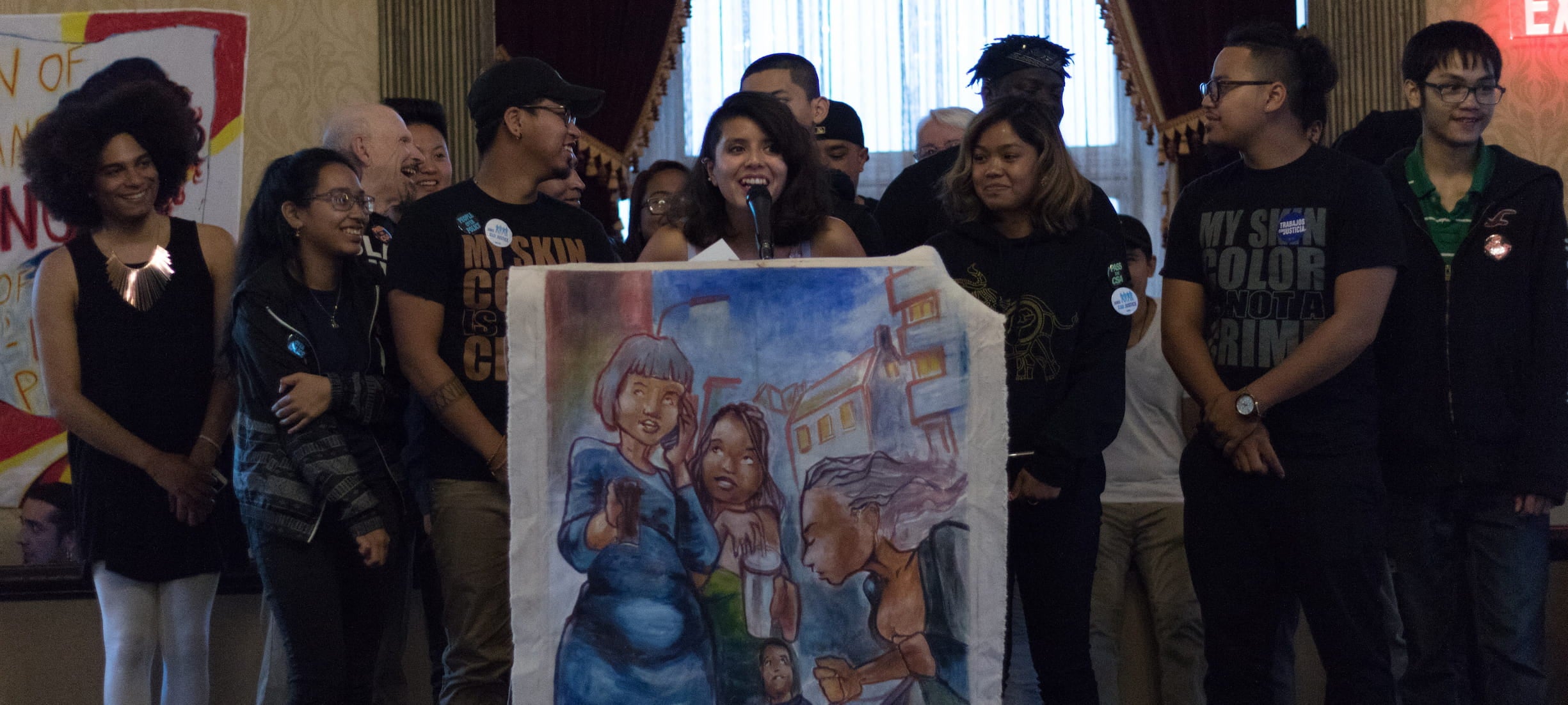

Image 41.07.02 — Providence Youth Student Movement members celebrate the 2017 passage of the Community Safety Act, including Justice Gaines (far left), Vanessa Flores-Maldonado (center), Linda Heng (third from right), and Daniel Chhum (second from right).

Created date, created by Name, Title Italicized. Credit line indicating where the image is from. Metadata ↗

“The Future We Want”: The Journey Toward Abolition

Despite the limits of legal reform, the CSA campaign was, as Vanessa says, “a building block to get to abolition.” 11 The process of organizing the CSA campaign deeply transformed the youth organizers. It offered them an opportunity to reflect on their experiences with racial profiling and criminalization, define community safety, and change city laws. Justice elaborates:

“Even if the bill was, like, a reform, in those meetings, we were constantly articulating the future we want for each other, and for ourselves,

and in our activism… [We talked] about the vision we want for ourselves, and

the vision that youth of Providence want for themselves, and, like, [what]

Southeast Asian youth want for themselves. And, like, that, to me, felt really powerful.” 12

Still rooted in its Southeast Asian history and origins, PrYSM has now evolved into an abolitionist organization committed to developing mutual aid networks in Providence. Most of its members are LGBTQ+, Black, Brown, and Southeast Asian middle and high school students who work in solidarity with each other as they continue to organize residents and build community-run projects in Providence. The youths’ sheer resilience, creativity, and commitment to community safety are best summed up by Daniel, who states that at PrYSM, “We’re gonna connect with each other. We’re gonna build with each other. We’re gonna love each other. And we’re gonna just keep going in any way possible.” 13

Glossary terms in this module

abolition Where it’s used

The belief in and practice of finding solutions to social issues beyond relying on the police. Abolition understands that marginalized communities are more often harmed by policing than protected by it. Instead of racially profiling and criminalizing communities, abolition transforms societal problems at their root by providing communities with basic needs, such as housing, healthcare, education, food, and clean air and water. Rather than investing in policing and prisons, an abolitionist vision invests in the basic needs of communities which create the conditions for safer, healthier lives.

community organizing Where it’s used

Getting everyday local people to come together, identify the issues that most affect their communities, and create solutions and actions for positive change.

community safety Where it’s used

The protection of people or a community without using the police, such as pooling resources, creating support networks, and developing practices of care for each other.

criminalization Where it’s used

The act of perceiving and portraying vulnerable and marginalized groups as a threat to public safety.

legal reform Where it’s used

Changes to laws–such as bills, acts, and legislation–that are designed to address problems and inequities in society.

mutual aid Where it’s used

A system in which community members collaborate and share resources to support each other’s needs. Mutual aid networks are characterized by generosity, solidarity, and care. They are a form of neighborhood activism that challenges the shortcomings of state institutions who fail to keep communities safe.

racial profiling Where it’s used

The unconstitutional practice of law enforcement officials who target, harass, and discriminate against individuals for suspicion of crime based on their race, ethnicity, religion, or nationality.

solidarity Where it’s used

A political, cultural, and collective stance that recognizes the mutual responsibility and support that is necessary to achieve change. Solidarity taps into the power in numbers and considers the collective interests of communities.

Endnotes

1 Justice Gaines, interview with May C. Fu and Katherine H. Lee, July 20, 2023.

2 Gaines, interview, July 20, 2023.

3 Ibid.

4 Daniel Chhum, interview with May C. Fu and Katherine H. Lee, July 25, 2023.

5 Vanessa Flores-Maldonado, interview with May C. Fu and Katherine H. Lee, July 21, 2023.

6 Flores-Maldonado, interview, July 21, 2023.

7 Gaines, interview, July 20, 2023.

8 Chhum, interview, July 25, 2023; “Community Defense Project,” Providence Youth Student Movement, accessed June 28, 2024, https://www.prysm.us/cdp.

9 Providence Youth Student Movement, “Community Defense Project Flyer,” Facebook, April 22, 2016, https://www.facebook.com/CommunityDefenseProject/photos/pb.100071510396259.-2207520000./487252601484428/?type=3.

10 Gaines, interview, July 20, 2023.

11 Flores-Maldonado, interview, July 21, 2023.

12 Gaines, interview, July 20, 2023.

13 Chhum, interview, July 25, 2023.